The Warren Commission and the Skepticism

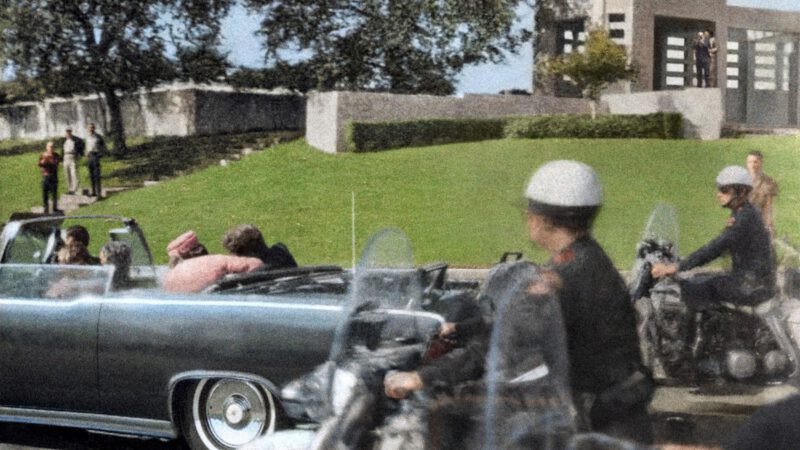

Soon after the assassination of JFK, it became clear to Lyndon Baines Johnson, the new president, that an independent investigative committee had to be established. There were too many uncertainties, and the Texan felt that the American people would demand a thorough investigation. From day one, there was a lot of distrust in public opinion. Soon after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Warren Commission began their investigation.

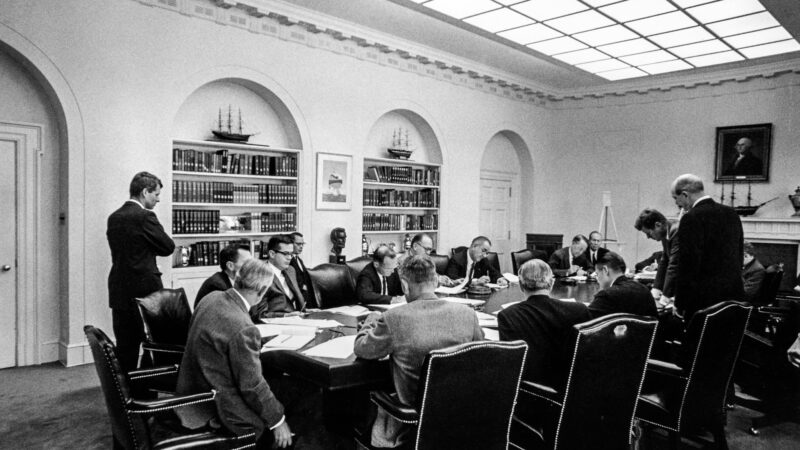

Johnson found a suitable chairman in Chief Justice Earl Warren of the Supreme Court. Warren, the man who had sworn in Kennedy almost two years earlier, did not actually aspire to a seat on the committee. Even after being asked by several high-ranking individuals, including Robert Kennedy, he continued to refuse. Johnson eventually persuaded Warren by appealing to his patriotic sentiments: ‘I told him that without a proper investigation, people would think that Cuba or the Soviet Union was responsible for Kennedy’s murder. And what consequences that would have for our country, possibly even a nuclear war. Warren was moved at that point. He accepted the task.’ In addition to the chairman, the committee included two senators, two members of the House of Representatives (including future President Gerald Ford), a former director of the CIA, and the ex-president of the World Bank. The choice of the former CIA director was particularly noteworthy: Allen W. Dulles had been dismissed by Kennedy in September 1961 as the head of the intelligence agency after the fiasco in the Cuban Bay of Pigs (more on that here).

One of the mentioned senators was Richard Russell, who, like Warren, initially had no interest in serving on the committee. ‘I don’t have time,’ Russell said, as revealed in a phone conversation between the senator and Lyndon B. Johnson that surfaced in the 1990s. ‘And besides, I don’t like Earl Warren.’ Johnson’s response left nothing to be desired: ‘Then you make time. It won’t cost us much effort, anyway. All we have to do is evaluate a report from Hoover, a report that’s already been made.’ J. Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI and a sworn enemy of the Kennedy brothers, had not yet completed his report at that time. However, his intentions were clear, as revealed in another recorded phone conversation just after Kennedy’s assassination: ‘What I’m most concerned about is public opinion. We need to disclose something that will convince people of Oswald’s guilt.’

In September 1964, the Warren Commission released an 888-page report, followed two months later by an additional 26 volumes containing 552 testimonies and over 3100 pieces of evidence (the so-called 26 Volumes of Hearings & Exhibits). The main conclusion was that Lee Harvey Oswald was the perpetrator. The commission referred in the report to his stay in the Soviet Union and his admiration for Cuba and Castro. Oswald was portrayed as a peculiar loner who had acted entirely on his own. There could be no talk of a conspiracy.

The conclusions were quickly challenged by critics who argued that the commission had overlooked many obvious clues. There were too many contradictions and indications that were clearly inconsistent with the drawn conclusions. Timelines didn’t match, bizarre incidents were insufficiently investigated, and where the commission encountered problems, issues were ignored, and so on. Over 85 percent of the American population no longer believes in the story presented by the Warren Commission in 1964. According to this substantial majority, Oswald could not have acted alone. And if this alleged perpetrator really had assistance, we can definitively speak of a conspiracy.

After the Warren Commission

One of the early opponents of the findings of the Warren Commission was Mark Lane, a well-known lawyer from New York who briefly represented the interests of Marguerite Oswald in the 1960s. In 1966, Lane wrote a book about the case, “Rush To Judgment.” Many followed suit. Books like “The Death Of The President” by William Manchester delved deeper into the assassination, but as of 2012, there is an enormous amount of literature exploring the smallest details and a wide range of theories—often far-fetched, but also thorough studies with theories that cannot be easily dismissed.

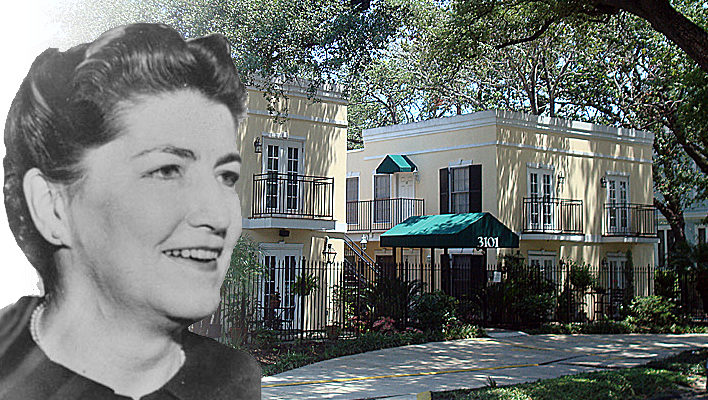

In 1966, District Attorney Jim Garrison from New Orleans began his own investigation into the murder. In March 1967, successful businessman Clay Shaw was arrested, suspected of being an accomplice to the conspiracy. He was alleged to have ties to the CIA and to have participated in the plotting of the murder plans with individuals like Guy Banister and David Ferrie. On January 29, 1969, the case went to trial, and the jury took less than an hour to acquit Shaw; Garrison lacked sufficient hard evidence. It would be the only trial in the case of Kennedy’s assassination. The 1970s then arrived, the years of government committees. First was the so-called Rockefeller Commission, chaired by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, which investigated CIA activities within the U.S. The Church Committee, led by Senator Frank Church, soon took over with a much broader focus; now, all government operations related to intelligence activities were under scrutiny. The sub-investigations into controversial plots aimed at the assassination of foreign leaders like Cuban Fidel Castro and Congolese Patrice Lumumba became the most famous. The committees released their reports in 1975 and 1976.

In 1979, the final report of the United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) followed, the House of Representatives’ investigative committee that, starting in 1976, examined the assassinations of JFK and Martin Luther King. Conclusions drawn: Oswald was at least involved and fired three shots, but there was likely a second shooter, hence a conspiracy. Nothing meaningful could be said about the identity of those involved. The committee informed the Department of Justice of its suspicion that the mafia knew more about Kennedy’s murder, but unfortunately, no adequate action was taken. Nevertheless, skeptics of the ‘lone assassin theory’ finally felt taken seriously. There was now an official government investigation with conclusions supporting their theories, showing that Lee Harvey Oswald was not solely responsible for President Kennedy’s assassination.

These investigations and related testimonies indirectly led to the deaths of mafia figures Sam Giancana (1975), Johnny Roselli (1976), and Charles Nicoletti (1977). Men who died shortly before they could testify. However, they were not the only victims. On the exact same day as Nicoletti, George De Mohrenschildt died under suspicious circumstances in Palm Beach, Florida. Oswald’s best friend in his last year of life supposedly committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth with a rifle, according to the official cause of death. Upon further investigation, it was revealed that it was not possible to pull the trigger with the long rifle in the mouth. De Mohrenschildt also had an invitation on his doormat to testify before the House of Representatives committee, but it never came to pass.

Even members of the Warren Commission became skeptical of their own findings in the late 1970s. Senator Richard Russell stated that he was no longer certain whether Oswald had acted alone, and political adviser John McCloy indicated in an interview that he no longer believed there was no evidence of a conspiracy.

More on the Warren Commission here.

2 thoughts on “The Warren Commission and the Skepticism”