James Jesus Angleton: sabotaging the investigation

When espionage activities were detected, a spy could be arrested; however, it was much more effective and interesting to keep him under control and observation to learn more about his knowledge, contacts, and sponsors. During the days of John F. Kennedy, at the height of the Cold War, many such counter-espionage activities were carried out in the Soviet Union. James Jesus Angleton (1917-1989) was the head of the Counterintelligence Staff within the CIA at that time.

Angleton spent part of his youth in Italy. In 1941, he graduated from Yale University, and during and after World War II, he worked in various European countries for the OSS. Shortly after the establishment of the CIA, Allen Dulles appointed him as the head of the counterintelligence division, a position he held until the end of his CIA career. Angleton’s major success came in 1956 when he obtained a transcript of a speech by Nikita Khrushchev in which the Soviet leader criticized his predecessor Stalin, who had died only three years earlier, as an “extremely egocentric sadist who could sacrifice anything and anyone for his own power and glory.” The text caused more trouble for international communism than the CIA had ever imagined. Investigative journalist Tim Weiner portrays Angleton in his great book Legacy of Ashes as a man who was drunk every day after lunch, a man with a mind like an impenetrable maze. Despite his unstable personality, he passed judgment on every operation and every agent the CIA deployed against the Soviets for twenty years. “He led the CIA’s missions against Moscow through a dark labyrinth,” Weiner wrote.

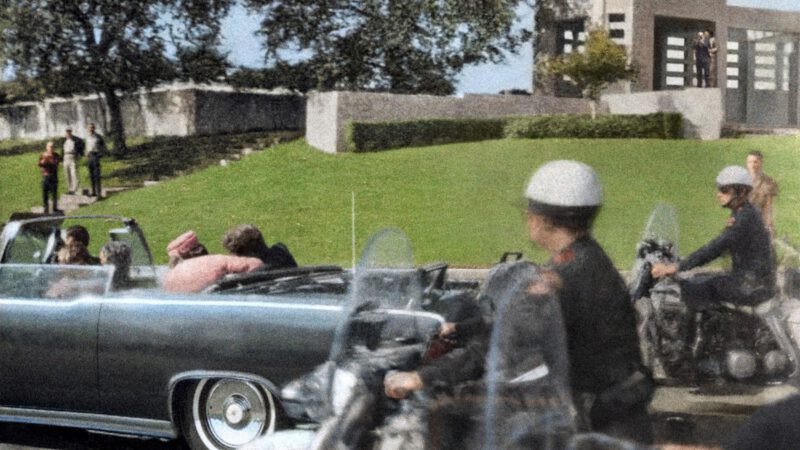

When the new head of the CIA’s secret service, Richard Helms, visited the president at the White House on Tuesday, November 19, 1963, he had a Belgian-made semi-automatic machine gun in his bag. The weapon was a war trophy: the CIA had intercepted 300,000 weapons that Fidel Castro had intended to smuggle into Venezuela. The recording equipment installed by Kennedy in the Oval Office flawlessly captured the words with which Helms and Kennedy concluded their brief meeting. “I’m glad the Secret Service didn’t catch us bringing a gun in here,” Helms said. “Yes,” Kennedy responded with a grin, “that does give me a feeling of security.” Three days later, while having lunch with CIA Director McCone, Helms received the terrible news. Kennedy had been shot. “The tragic death of President Kennedy demands that we sharpen our focus on all sorts of unusual developments,” Helms wrote on the same day in a message to all CIA posts worldwide. Helms then entrusted the case of Oswald to John Witten, the man who coordinated all CIA secret operations in Mexico and Central America. James Angleton was furious: he had expected to handle the case, and now his adversary Whitten was taking the credit. From that moment on, Angleton did everything in his power to sabotage him. He erected barriers for Whitten, criticized his work, and frustrated his attempts to uncover the facts. Within a few weeks, Angleton got his way. Whitten was removed from the case.

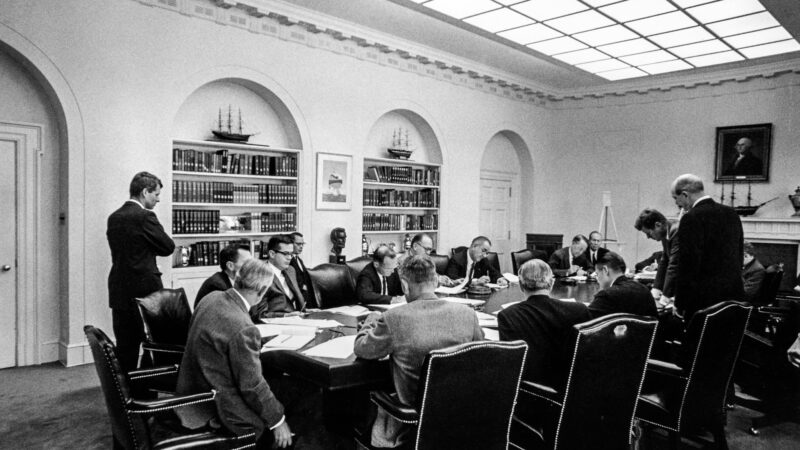

From that moment on, Angleton became the central point of contact for all matters the Warren Commission needed the CIA for. Later, Angleton revealed that he informally discussed the assassination with a member of that commission, his former boss, Allen Dulles. As turned out when many new documents were released in the 1990s, Dulles maintained good contacts with high-ranking individuals within the intelligence service long after his retirement. It became clear that Dulles had coached CIA agents on how to respond to difficult questions from the commission. Dulles taught his former subordinates how to insist that Lee Harvey Oswald had never had anything to do with the CIA. This became evident after the revelation of an internal memo in 1997. CIA agent David E. Murphy wrote that he spoke with Dulles on April 11, 1964, about the murder case: “I agreed with him that a cautious, well-considered denial of any CIA involvement with Oswald seemed most appropriate.” The CIA apparently had something to hide. Why were they lying? Why did the CIA have to be so careful in its statements? Why was Dulles so active in manipulating his former subordinates? Incidentally, Dulles was not the only one who treated his integrity indifferently. While every effort was made to keep all information confidential, Commission member Gerald Ford regularly conversed with high-ranking FBI officials about the progress of the investigation. Over time, the objectivity of the Commission’s final conclusions in 1964 became an increasingly significant question mark.

John Whitten later told the House Select Committee on Assassinations that he found Angleton’s investigation particularly poorly executed. Whitten complained to Helms, but he was not heard. Whitten to the HSCA: “I think Angleton’s attempts to sabotage the investigation have to do with his connections to the mafia. It’s no coincidence that he once thwarted investigations into secret mafia accounts in Panama. Angleton ignored a possible Cuban connection to the murder from the very beginning and was only concerned with his tunnel vision: Oswald’s life in Russia. If I had been allowed to lead the investigation, I would have paid more attention to the CIA base in Miami. I think they know more about the murder.”

James Angleton was not only heavily criticized by Whitten. The man became increasingly obsessed with his own delusions – at one point, half the world was working for the Russians, including the CIA director. Angleton was insane, as stated later in a CIA evaluation. He poisoned the atmosphere, sabotaged heads of stations throughout Europe, and undermined the cooperation of intelligence services. Within the CIA, a small but determined group of employees began to resist. But no matter how many careers and lives he destroyed, Angleton was allowed to stay. “Angleton was our downfall,” said someone who led anti-Soviet operations in the 1960s and 1970s. Until the paranoid, alcoholic spy hunter crossed a final limit. In 1974, he was forced into retirement.

Links:

The Warren Commission and-the-skepticism

More on Dulles, Cabell and Bissell – other important CIA-officials