The Bay of Pigs invasion

On April 17, 1961, the invasion in the Bay of Pigs took place. First, I would like to introduce three top officials of the CIA. Then more on the failed Bay of Pigs invasion will follow.

Allen Dulles (1893-1969) was an American lawyer who became the first civilian director of the CIA. He is its longest serving director to date. Dulles came from a well-known American family. His brother was the Secretary of State in the 1950s, and both his grandfather and an uncle had also held that position. After his studies, the avid pipe smoker worked in the 1920s at embassies in various cities, including Vienna, Paris, Berlin, and Istanbul. Even in those years, he actively collected information for various intelligence agencies in the United States. During World War II, he lived in Bern, where he became the director of the local OSS (Office of Strategic Services) branch. For that precursor to the CIA, he became the key figure when it came to gathering intelligence on the Third Reich. After its fall, he advised President Truman to create a successful intelligence service by consolidating the various agencies.

After his appointment as CIA director, Dulles organized the CIA operations Ajax and Success. The first project was a successful coup in Iran, where, thanks to American intervention, Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh was overthrown in August 1953. The coup was considered the CIA’s biggest triumph up to that point, a grand American victory. The change in direction would eventually lead to chaos in the streets of Tehran, disorder that would ultimately turn against the United States, but Dulles was not concerned about that in 1953. The United States benefited from the new political situation in Iran: the oil industry in the country was no longer nationalized. The cash registers at the American Gulf Oil began to ring again. The second project took place in Guatemala, where President Árbenz was ousted in June 1954 after a military coup. This time, the reason for the campaign was not oil but tropical fruit. The United Fruit Company, one of the largest landowners in Guatemala, was threatened with expropriation. The American company, best known in the Netherlands for Chiquita bananas, had enormous political and economic influence throughout Central America. In the 1930s, Allen Dulles himself sat on the board of United Fruit, and now, fifteen years later, that same Dulles quickly organized a liberation army to secure the company’s future – and thus the power of the United States in the region. The takeover in Guatemala plunged the intelligence service into a struggle that would last for forty years, but it did establish a right-wing government willing to defend the interests of United Fruit. Within the CIA, Operation Success was seen as the epitome of a well-executed action; critics of US foreign policy consider the operation primarily an example of America’s lack of respect for human rights and democracy.

The two campaigns were followed by many other projects that were often far less successful. The CIA became particularly active in Asia and the Middle East in the 1950s. Islamic leaders who did not pledge allegiance to the US were ousted – the CIA supported, among others, the Ba’ath Party in Iraq, ultimately helping the promising assassin Saddam Hussein come to power. In other places, countries had to be liberated from their colonizers or their communist governments. A prime example is the utterly failed CIA campaign against Indonesia under Sukarno.

Allen Dulles thus had busy years full of political, psychological, and paramilitary missions. Under Eisenhower, who was often misled and only partially aware of what the CIA was up to, 170 new major secret operations were carried out in 48 countries in the 1950s. The team, including people like David Atlee Phillips, Howard Hunt, and David Morales, considered themselves invincible. And then came Cuba.

For the next challenge, liberating the Cuban people from Fidel Castro, plans were built on those executed in Guatemala. New men like William Harvey and Ted Shackley were added to the team. Dulles wanted to develop a powerful propaganda offensive, work on a resistance group in Cuba, and establish a paramilitary force outside Cuba. And, it was quickly decided, a prerequisite for success was the assassination of Castro. This is where the collaboration with organized crime began. In the midst of these hectic times, the country got a new president.

In the eight years Dulles was in power, unimaginable damage was done to the intelligence service. Author Tim Weiner writes: ‘He despised analytical details, had a preference for secret operations, and systematically misled the President of the United States. It would prove disastrous for the CIA.’ On January 5, 1961, in his last weeks as president, Eisenhower received a comprehensive report from the Presidential Advisory Board. The board called for a complete overhaul of the CIA, and the main recommendation was to part ways with Director Dulles. ‘When it comes to the intelligence service, I have suffered an eight-year defeat,’ Eisenhower later said. However, one of Kennedy’s first presidential decisions was the reappointment of Dulles, on the advice of father Joe Kennedy. Senior knew that Dulles knew some deep family secrets, so the decision primarily served as political and personal protection.

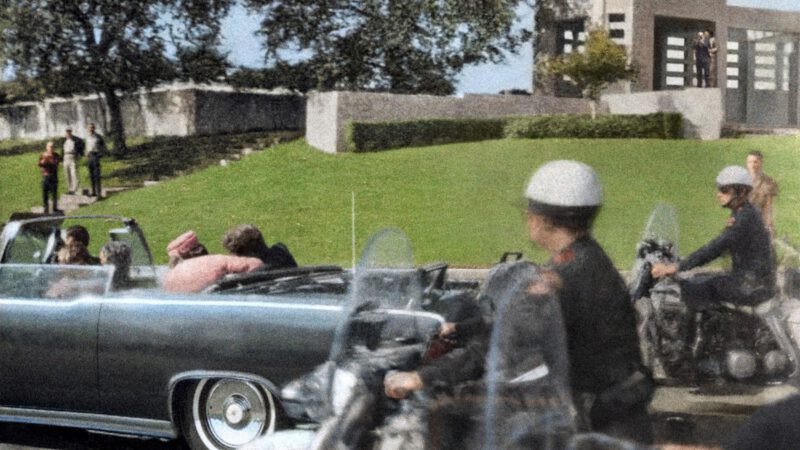

The second man at the CIA for all those years was Lieutenant General of the Air Force Charles Pearre Cabell (1903-1971). He was born in Dallas and held various high positions within the US government before becoming Dulles’ right-hand man in 1953. His brother Earle Cabell was the mayor of Dallas from 1961 to 1964, and as such, he was the highest-ranking official of the police there and the person responsible for the presidential entourage on the fateful day in November 1963. Many researchers, including James H. Fetzer, believe that the two brothers were involved in the conspiracy against Kennedy. Fetzer wrote in “Assassination Science”: ‘They had a motive and, from their positions, sufficient means and opportunities. On November 22, 1963, they finally had the chance to put them into action.’

Richard Mervin Bissell Jr. (1910-1994) was the Director of Plans under Dulles. He led a significant CIA division responsible for so-called Black Operations, the organization’s most secret operations with often dubious ethical or legal character. Bissell, previously involved in the Marshall Plan in Europe, joined the CIA in the early 1950s at the recommendation of Frank Wisner, the then head of the intelligence agency. In 1954, Bissell became responsible for the development and operation of U-2 spy planes – gliders with a jet engine. Two years and nineteen million dollars later, President Dwight Eisenhower gave permission to fly over cities like Moscow and Leningrad for the first time. The project was a great success: according to Bissell, later, 90 percent of all information about the Soviet Union was obtained through aerial photographs taken by U-2s. When Wisner, after a nervous breakdown and depression, could no longer function at such a high level, Dulles appointed Richard Bissell as his successor on January 1, 1959, coincidentally the same day Castro came to power in Cuba. After Dulles’ successful coups in Iran and Guatemala, new times began. At least four foreign military operations took place under Bissell’s leadership. In 1961, the governments of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in Congo and dictator Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic were overthrown with CIA support – both leaders were assassinated. In 1963, coups followed against General Abd al-Karim Kassem in Iraq and Ngo Dinh Diem, the leader of South Vietnam. These campaigns also ended fatally for the fallen politicians.

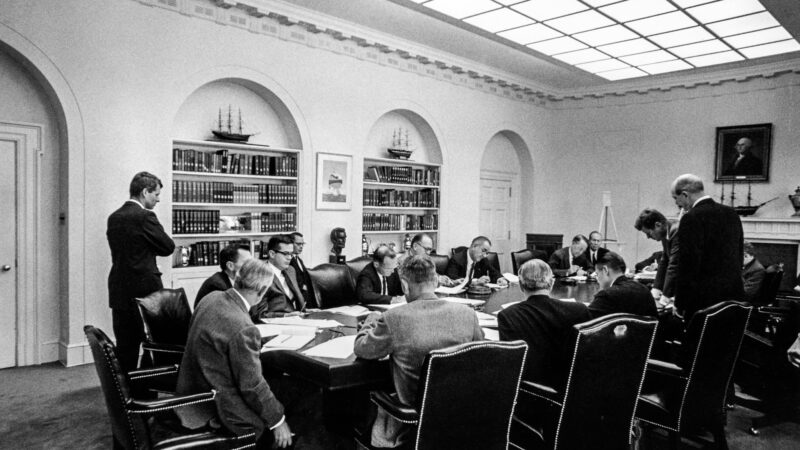

The Bay of Pigs invasion

However, Bissell’s main target was the Cuban leader. On December 11, 1959, Bissell wrote a memo to his boss Dulles: ‘Serious consideration must be given to the elimination of Fidel Castro.’ Within a month, a special unit was formed, the team that had been so successful in Guatemala before. On November 18, 1960, ten days after the presidential elections, Kennedy received all the plans from Dulles and Bissell at his residence in Palm Beach, Florida. For the first time, he learned about the planned invasion in Trinidad, Cuba, an invasion that Eisenhower had never approved, but Kennedy did not know that. What he knew was only the part that Dulles and Bissell told him. Kennedy rejected the original plan. In March 1961, he asked Bissell for a modification. He simply found the chances of success too small. The Bay of Pigs, a more remote location, was now chosen. Dulles and Bissell immediately realized that the new plan had a smaller chance of success, but they thought Kennedy would realize this in time. And during the invasion, he could still adjust appropriately. Key CIA officials like Jake Esterline and Jack Hawkins were not happy with the new, risky plan. Esterline later said, ‘On April 8, we went to Bissell. We had no confidence in the invasion anymore. We offered our resignation, but it was not accepted. Bissell ordered us to stay.’ On April 10, Bissell told Robert F. Kennedy, the new Attorney General, that the chance of success was only 66 percent. Nevertheless, the president hesitated. When he heard on April 14 that Bissell wanted to deploy sixteen planes, the president reduced this number by half. Kennedy wanted a quiet coup. The CIA watched and could do nothing – only hope that he would change his mind during the invasion. Unfortunately, that did not happen.

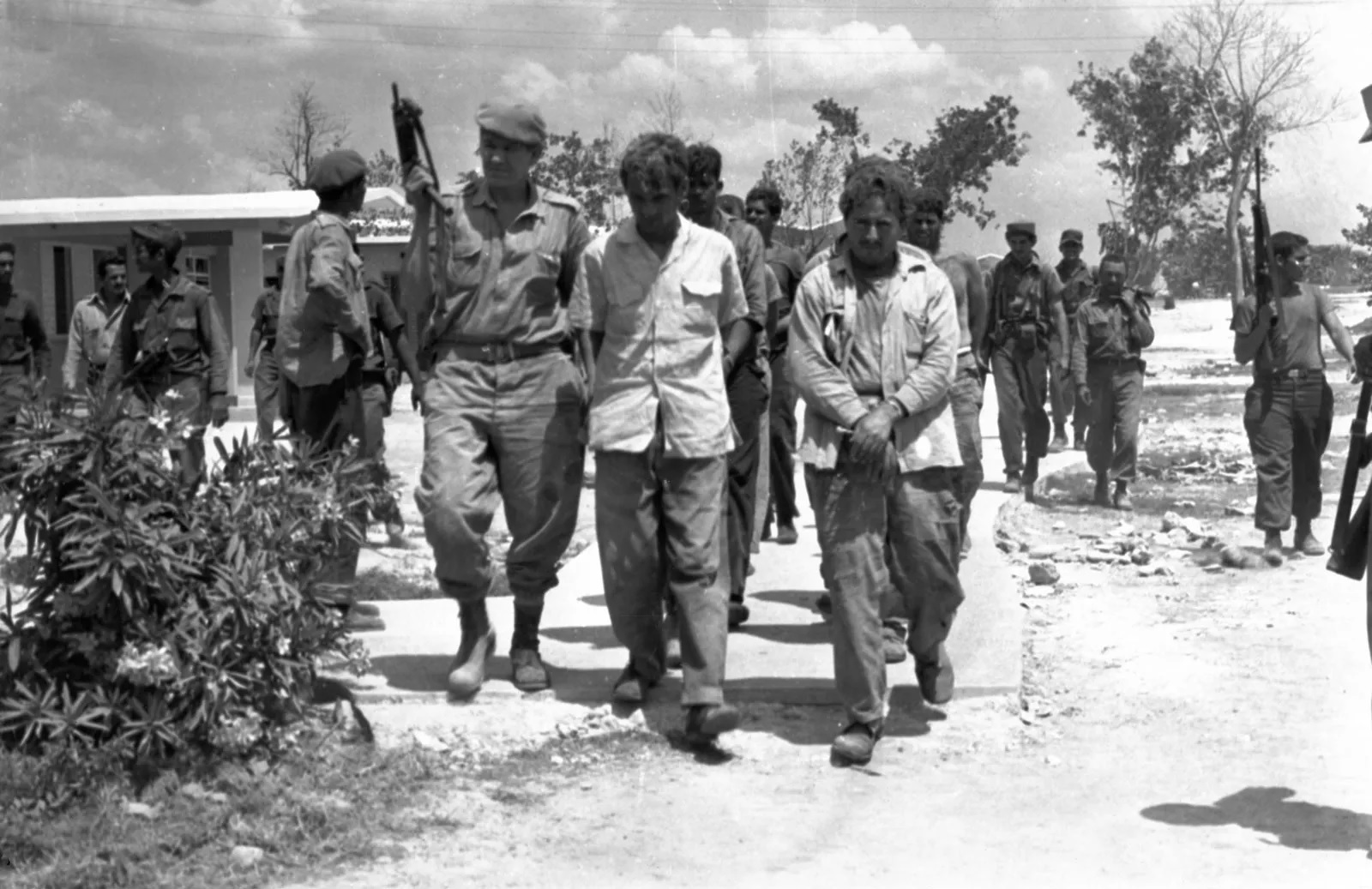

On April 17, 1961, the invasion in the Bay of Pigs took place. Since Allen Dulles was in Puerto Rico during the invasion, Charles Cabell was the responsible man at that time. According to the original plan, Cuba’s military airports would have been bombed by the US two days earlier, but this part was scrapped at the last minute on Kennedy’s orders. In the heat of the battle, Kennedy was called by Deputy Director Cabell, informing him that the engines of the American planes were already warming up on the aircraft carriers just off the coast of the island. The imminent failure of the invasion could be reversed within minutes – Kennedy just had to give his permission. However, the president refused to comply with this request, and the battle in the Bay of Pigs was definitively decided in favor of the Cuban government after three days. Cabell would later describe the president as a traitor. The Cuban exiles living in the United States suffered a heavy defeat. Of the 1,300-strong invasion force, 90 were killed, and 1,189 were captured.

Dismissal

After the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, Kennedy took part of the responsibility upon himself and part on the intelligence service. Kennedy reportedly told Bissell, ‘In a parliamentary government, I would have to resign, but our system of government cannot do that. So I have to bid farewell to you.’ Director Allen Dulles, his right-hand man Charles Cabell, and Richard Bissell were suspended. They had failed to provide accurate and realistic information to two presidents and two administrations. Men who had been on a huge pedestal, active in the CIA since World War II, now bid farewell one by one. Dulles retired in September 1961; the new director was Republican John McCone. Cabell followed in January 1962 and was replaced by Marshall Carter. Bissell left a month later and was succeeded by the man with whom he had not been on good terms for years: Richard Helms.

The president did not make friends with his sanctions. The Bay of Pigs invasion and the consequences of its failure are very important elements in the investigation into the true circumstances of Kennedy’s assassination.

Photo above:

U.S.-backed Cuban exiles captured during the Bay of Pigs fiasco, Cuba, 1961.

© Sovfoto/Universal Images Group/Shutterstock.com

Dulles in the Warren Commission: more on that here

A lot of information about the Bay of Pigs invasion here

4 thoughts on “The Bay of Pigs invasion”