The military–industrial complex

Wikipedia on the military-industrial complex: “The expression military–industrial complex describes the relationship between a country’s military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the relationship between the military and the defense-minded corporations is that both sides benefit—one side from obtaining weapons, and the other from being paid to supply them. The term is most often used in reference to the system behind the armed forces of the United States, where the relationship is most prevalent due to close links among defense contractors, the Pentagon, and politicians. The expression gained popularity after a warning of the relationship’s detrimental effects, in the farewell address of U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 17, 1961.”

“I look forward to a future in which our country will match its military strength with our moral restraint, its wealth with our wisdom, its power with our purpose.”

John F. Kennedy in October 1963 during a speech in Massachusetts

The last morning

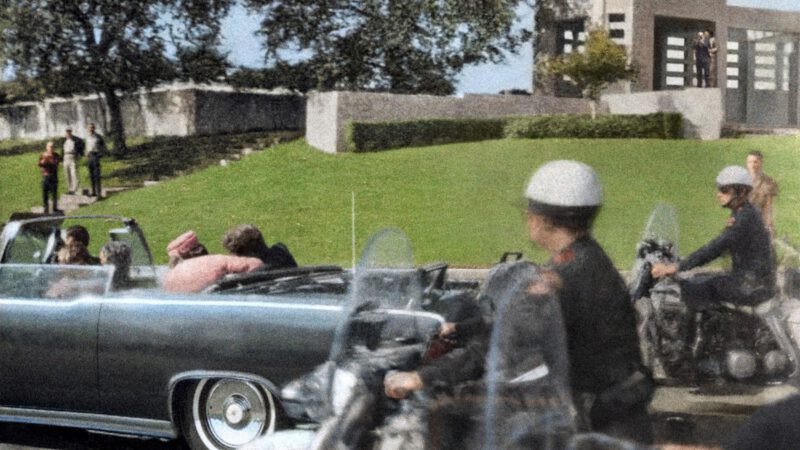

“Two years ago, I introduced myself in Paris by saying that I was the man who had accompanied Mrs. Kennedy to Paris. I’m getting somewhat that same sensation as I travel around Texas. Nobody wonders what Lyndon and I wear…” With this joke, which was greeted with laughter, Kennedy began his speech to representatives of the Chamber of Commerce at the Texas Hotel in Fort Worth on the last morning of his life. It was November 22, 1963, 9:00 AM.

Kennedy continued his speech with an ode to the city of Fort Worth. “And I want to say a word about that pledge here in Fort Worth, which understands national defense and its importance to the security of the United States. During the days of the Indian War, this city was a fort. During the days of World War I, even before the United States got into the war, Royal Canadian Air Force pilots were training here. During the days of World War II, the great Liberator bombers, in which my brother flew with his co-pilot from this city, were produced here. (…) So wherever the confrontation may occur, and in the last three years it has occurred on at least three occasions, in Laos, Berlin, and Cuba, and it will again, wherever it occurs, the products of Fort Worth and the men of Fort Worth provide us with a sense of security. (…) These are not simple efforts. They require sacrifices from our fellow countrymen. We live in a very dangerous and uncertain world. No one expects better times soon; certainly not in this decade. Maybe we have to wait until the next century. But we can be proud because all around the world, we support countries fighting against communism. Without the United States, South Vietnam would capitulate tomorrow. Without us, various alliances fighting against a communist enemy would have to surrender tomorrow. NATO would not exist without us, and European countries would be divided and turn away from the world outside them without us. We bear a tremendous burden, but we are far from weary. The balance of power is still on the side of freedom. We are still the keystone in the arch of freedom, and I think we will continue to do as we have done in our past, our duty, and the people of Texas will be in the lead. So I am glad to come to this State, which has played such a significant role in so many efforts in this century, and to say that here in Fort Worth you people will be playing a major role in the maintenance of the security of the United States for the next 10 years. I am confident, as I look to the future, that our chances for security, our chances for peace, are better than they have been in the past. And the reason is because we are stronger. And with that strength is a determination to not only maintain the peace, but also the vital interests of the United States. To that great cause, Texas and the United States are committed.”

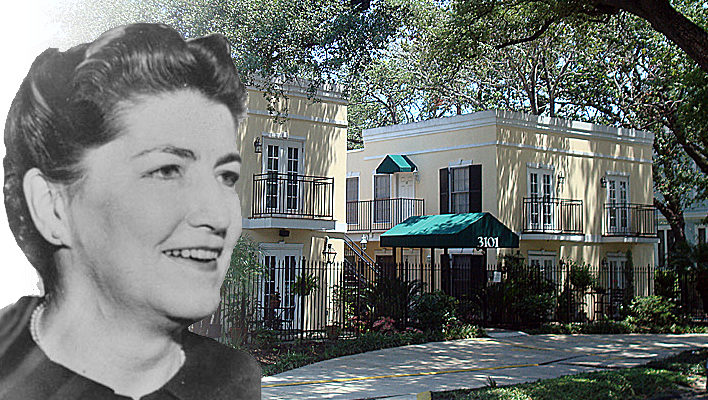

During his speech, Kennedy boasted about all the military efforts of his administration. The Department of Defense had no time to be bored during this hectic time at the height of the Cold War. The military and the defense industry seemed to thrive amid all the violence in the world. And yet, there was much dissatisfaction. The future did not seem bright under Kennedy. Authorities claim that there were concerns about Kennedy’s soft side: he preferred to peacefully resolve issues with the communists, especially those in Cuba and Vietnam, without escalating them into hotspots. A large group of researchers suspects representatives of these industries of involvement in the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Numerous books have been written with plausible theories, and even in the most famous film about the case, Oliver Stone’s JFK, individuals within this ‘iron triangle’ do not come off lightly.

Lyndon B. Johnson was cut from a different cloth than his predecessor. Many cash registers in the United States would ring like never before after Kennedy’s death. Officials from the Department of Defense, military personnel, and those in power in the defense industry might just have a murder on their conscience.

Complex relations

The Roman Praetorian Guard was a special military unit that served as the imperial bodyguard around 2,000 years ago. In its nearly 400 years of existence, this powerful group is known to have assassinated at least twelve Roman emperors. If they were displeased with the policies of the ruler, assassination was the most logical solution. This phenomenon is timeless: military commanders who lead in battles, taste power, and then struggle to relinquish authority to civilian governance. Decisive men who can leverage their influence and often get their way, be it by bribing politicians or simply eliminating them.

How objectively can crucial political decisions be made when there is substantial money to be made from a particular choice? Do we all desire as much peace on earth as possible, or is a portion of us content with yet another lucrative war? Several researchers have written impressive books about the situation in America in the first decades of the twentieth century, highlighting the unhealthy conditions that, according to them, worsened during World War II. Entangled interests with significant consequences on the world stage were commonplace. Consider President George W. Bush and his cabinet members Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, and Wolfowitz. They all earned considerable profits from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and almost all had close ties to military companies like Lockheed-Martin, KRB, Boeing, and Carlyle. Forty years earlier, Lyndon B. Johnson had extensive connections with the contractor and construction company Brown and Root, the organization that worked extensively for the U.S. military during the Vietnam War.

When an industry is powerful enough to put forth its own politicians—decision-makers who can also profit significantly from war and distress—dangerous political perspectives emerge. The United States was warned about this by the departing President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the country during World War II. On January 17, 1961, three days before John F. Kennedy succeeded him, he delivered his farewell speech to Congress and the American people, introducing the term ‘military-industrial complex.’ In essence, his words were: ‘An essential element in keeping peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction. The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved. So is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties and democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.’

These are significant words. Oliver Stone even began his film with them thirty years later. And over fifty years after Eisenhower’s speech, we can consider these words prophetic: the entangled interests have only increased. The annual budget of the Department of Defense has skyrocketed. In 1950, the military budget was a staggering 13 trillion dollars, equivalent to 120 trillion dollars in 2012. By 1961, it had already risen to 47 trillion dollars. After the Vietnam War in 1975, over 100 trillion dollars were spent, and in 2006, under Bush, the threshold of 500 trillion dollars was reached. Obama’s proposal for 2013 totaled 613.9 trillion dollars—more than five times as much as in 1950, adjusting for inflation.

The fact that the military and arms industry have gained so much influence over the years is only known to a few. Sustaining the wartime economy seems to be the dictum among the powerful. A second Pearl Harbor, where the United States was unexpectedly attacked by a hostile nation, should absolutely be prevented. Assembly and production lines had to be continuously operational so that America could swiftly engage in war when necessary. Be prepared for the worst. And, an argument from an industry representative could be: millions of Americans depend on the sector and defense contracts, so why shut down the market?

JFK and the military–industrial complex

Even the young Senator Kennedy, during his presidential campaign in 1960, sided with the Pentagon, as the Department of Defense in the United States is often called, referring to the pentagonal headquarters of the U.S. armed forces. He promised an increase in military spending. However, once elected, he changed his mind, partly because he claimed to have been misled by officials about the actual threat from enemy nations. Later, more authorities stated that there was a huge gap between the actual power of the Soviet Union and the power attributed to it by the military. Tom Gervasi wrote a book about it in 1987: The Myth of Soviet Military Supremacy. By creating a dangerous enemy, it was easy to generate support for substantial investments in defense. Shortly after his election as president, Kennedy complained about the incorrect intelligence that had been presented to him. Partly for this reason, he appointed someone from outside as the new Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, chairman of Ford Motor Company. The secretary would develop a very good relationship with the Kennedy brothers.

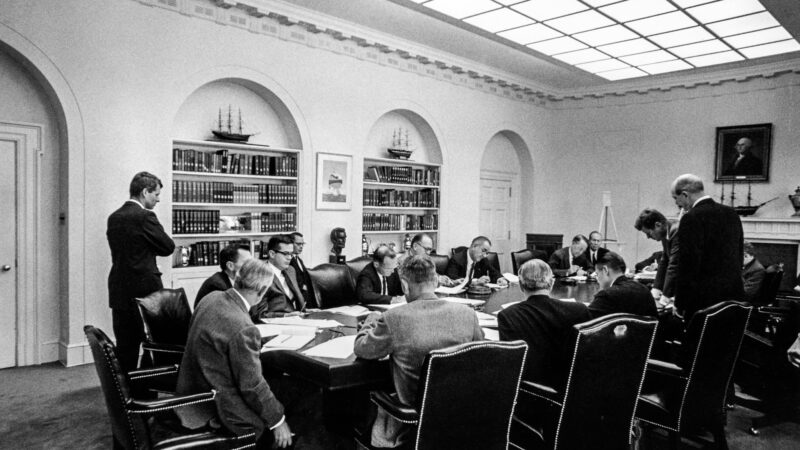

McNamara’s appointment brought about many changes immediately. In March 1961, Kennedy stated: ‘In January, we saw that immediate major changes were necessary. I have instructed the Secretary of Defense to reevaluate the entire strategy, capacity, commitments, and needs in light of current and future potential danger.’ Like with the CIA, Kennedy wanted to do things his own way, and the Pentagon had to adjust. The president had little regard for recently introduced tactics like counter-guerrilla strategy, flexible response, and the formation of special units. Especially not when he and his brother realized, after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, what the doctrines actually meant: a collective obsession with secret, clandestine operations, based on the ‘need to know’ principle, involving as few responsible leaders as possible. After the heavy defeat in that invasion, several things became clear to the president: he was misled, the government and the military were unhealthily intertwined, and the military-industrial complex was more powerful than he could have imagined. War should be a last resort for politicians. And if a war had become inevitable, it should be led by military personnel with clear objectives, without a hidden agenda or conflicting interests. Kennedy could no longer rely on either.

In June 1961, Kennedy signed two important new laws. National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 55 stipulated that the president held the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff responsible for all activities of the military, both in war and in peacetime. The leader of this body with commanders of the U.S. armed forces would thus have control over all activities at all times—no one else could pull the strings any longer. Since the Joint Chiefs of Staff fell directly under the president, Kennedy now had a much better understanding of what was going on. NSAM 57 dealt with a new division of paramilitary activities and responsibilities between the military and the CIA. The intelligence agency could only be involved in small secret operations; for larger matters, the military had to be involved for approval.

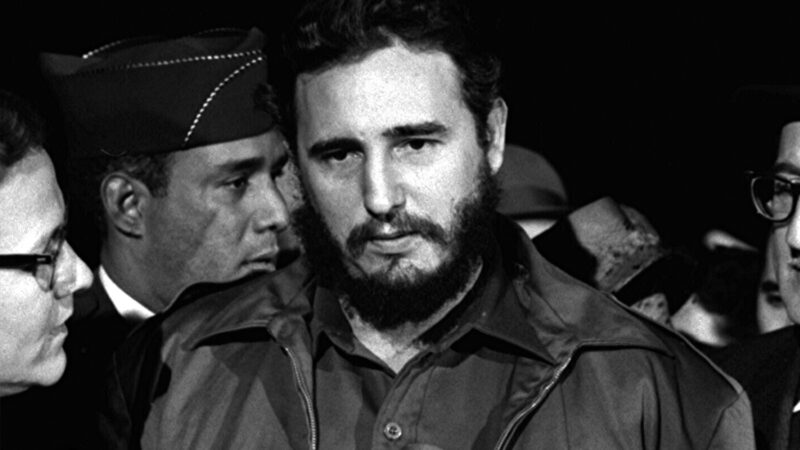

The CIA and the Pentagon felt severely restrained by the new laws. Their infallibility came to an end, despite the enormous interests at stake—especially financial gain. Kennedy cleaned house in the organizations, dismissing high-ranking CIA officials and replacing Lyman Lemnitzer, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In March 1962, Lemnitzer came up with the secret Northwoods project. He wanted to simulate terrorist actions within U.S. borders and blame the Cubans, thereby gaining public support for a war against Fidel Castro’s island. The dubious plan suggested, among other things, exploding an empty ship in Guantanamo Bay and then spreading a fake list of supposed victims. Plane hijackings were also considered, as well as terror in Miami and other cities in Florida. In the capital, bombs could be detonated at carefully chosen locations, with no hesitation to cause casualties. The plan, only released in 2001, is a good example of the approach the president detested. Lemnitzer had to pack his bags; he got a position in Europe. His replacement was Maxwell D. Taylor: a man whom the Kennedys held in high esteem and saw as a person of unquestionable integrity, sincerity, intelligence, and diplomacy. Again, it was time for a new direction: Kennedy wanted to shape the country to his liking.

He demonstrated this in the dispute with the steel industry in early spring 1962. The president was concerned about inflation due to rising costs, which posed a threat to the economy. The steel industry was crucial in the pursuit of price stability because an increase in steel prices had such a comprehensive effect on the entire economy. Kennedy asked the major steel companies not to raise their prices again and also asked the union to revise its wage demands. Both the unions and the companies eventually responded positively, and Kennedy was pleased. However, he rejoiced too soon. Ultimately, U.S. Steel, the largest company, did not adhere to the agreements. They raised the steel price by six dollars per ton. The next morning, Bethlehem Steel, the second-largest company, also announced a price increase. Other companies followed quickly. The actions posed a serious threat to Kennedy’s wage and price policy, the growth of the economy, Kennedy’s budget, and the trust that major unions had in him. JFK was furious and felt betrayed. He instructed the Department of Defense to cancel all orders to U.S. Steel in favor of companies that had not yet raised their prices. Public opinion rallied behind the president, and more and more steel companies announced that they would not increase their prices. Ultimately, U.S. Steel also capitulated. Too much was at stake now that all lucrative projects at home and abroad were in danger of going to the competition. Kennedy had made it clear once and for all who was in charge of American business. As described in the previous chapter, the oil industry would realize this shortly afterward. The list of Kennedy’s enemies was getting longer and longer.

In October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis occurred. Enemy missiles were only 150 kilometers from the American coast: the military and the CIA were unanimous and unyielding. Cuba had to be bombed, and a new invasion was absolutely necessary. The nonviolent deal that Kennedy ultimately struck with Nikita Khrushchev angered many in various offices. The president became a hero among the population, but in various capital offices, people were furious. And the reduction of military spending continued unabated in 1963. Kennedy continued to fuel the fire. In March, McNamara came up with a reorganization plan in which 43 military institutions would close within three years: 22 in the United States and 21 abroad. In late July, Kennedy enthusiastically spoke of the first steps toward the end of the Cold War, and a week later, England, the United States and the Soviet Union signed a treaty that would lead to a global nuclear weapons stop. A direct phone connection was established between Moscow and Washington. The developments differed greatly from the tough policy of the pre-Kennedy era, and military leaders did not hesitate to express their disapproval again.

Of great importance was also Kennedy’s decision to reassess the role of the United States in Southeast Asia. Was his, according to some, too soft policy fatal for him? Some researchers believe that the key to understanding the true culprits behind Kennedy’s assassination lies in investigating this.

JFK and Vietnam

After Kennedy’s death, Lyndon B. Johnson took over. He promised to continue the policy initiated by JFK, at least until the next elections. He kept that promise on some points; for example, Johnson was the one who ultimately pushed the civil rights laws through Congress. However, many other intentions of Kennedy were completely ignored. Four days after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson signed NSAM 273, the document in which massive intervention in South Vietnam was decided.

South Vietnam, the land of the unfairly elected fervent anti-communist Ngo Dinh Diem, was threatened by the so-called National Liberation Front, known to American soldiers as the Vietcong. This communist resistance and guerrilla group had started infiltrations since 1959. Initially, the United States provided only support and material to South Vietnam. Combat training was given to South Vietnamese soldiers, and Ngo Dinh Diem surrounded himself with American advisors. Kennedy followed the policy of his predecessor Eisenhower. He had been interested in Indochina early in his career. In 1956, he spoke about the security threat to countries like Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines if the red danger of communism were to flood Vietnam. In the period before his presidency, he often talked about appeasing third-world countries with economic aid to prevent them from falling under the influence of the Soviet Union and also communist China, if necessary intervening with force. Father Joseph Kennedy had become friends with Ngo Dinh Diem, and his son also developed increasingly closer ties in South Vietnam.

During Kennedy’s time in the White House, the number of American ‘advisors’ in the country continued to rise—by the end of 1961, there were already more than 2,200. In May 1962, the president announced that they were all trying to work towards a peaceful solution. Yes, they were occasionally involved in firefights, but according to Kennedy and Secretary of Defense McNamara, these cases were only in self-defense. The situation was more nuanced in reality. In October, the New York Times wrote, ‘In 30 percent of all combat missions in Vietnamese planes, Americans are at the controls.’ Meanwhile, the focus in Washington was mainly on the Soviet Union, Cuba, and Berlin.

But that changed in the hot summer of 1963. Kennedy received conflicting information and began to reconsider his policy. He was also concerned about Ngo Dinh Diem, whose policies were becoming increasingly unpopular. Some Buddhist monks set themselves on fire in protest against the regime. Resistance among the Catholic aristocracy also grew, believing that Diem stood in the way of potential peace talks with North Vietnam. The Americans decided not to intervene in the event of a coup. The U.S. ambassador, Henry Cabot Lodge, refused to talk to Ngo Dinh Diem any longer and openly supported high-ranking military officers known for their negative attitude toward the regime. Kennedy also loathed the dictator and approved plans that involved the return of a thousand American military advisors by the end of 1963. The president no longer wanted to be heavily involved in the conflict.

Ultimately, dissatisfied officers staged an armed coup in Saigon on November 1, 1963, led by General Duong Van Minh. Both Ngo Dinh Diem and his younger brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu (the head of the security service), lost their lives. The southern government had been overthrown. According to various studies, CIA officials were involved in the coup. No strange insinuation: they had had similar experiences in other parts of the world in the 1950s. Many years later, some evidence surfaced, but U.S. involvement is not 100 percent certain. The coup had been extensively discussed in the White House. Kennedy wanted to banish Ngo Dinh Diem as soon as possible. He only heard the next morning that the coup had ultimately become deadly. According to a witness, JFK was astonished and shocked three weeks before his own death. He found the murder repulsive. This opinion was not shared by many: most officials in the American capital were glad to be rid of the leader. Kennedy publicly praised Ambassador Lodge: ‘Thanks for a highly important presentation recognized by the entire government.’

The White House faced a choice: deploy a large American expedition and quickly resolve the problem in South Vietnam, as the Pentagon wanted, or simply withdraw and accept the criticism of the anticommunist military-industrial complex. The assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem seemed to strengthen Kennedy’s resolve to break free from the conflict. He wanted to limit American involvement—but only after the next elections, in November 1964. JFK knew that a new soft decision might be deadly for his eagerly desired reelection. He told his advisor Kenneth O’Donnell: ‘Ultimately, everyone will call me a communist. I don’t care about that. As long as it happens after 1964.’ In the fall of 1963, he already mentioned in a television speech: ‘This is an important struggle, even though it is fought far away. But ultimately, it is their war. Not ours. They must win or lose, not us.’ Fellow countrymen with financial interests in the military-industrial complex may have shuddered at those words in their living rooms.

Two days before the Dallas motorcade, after optimistic words from Robert McNamara about the situation in South Vietnam, Kennedy approved a plan to bring all Americans out of Vietnam by the end of 1965. With the document NSAM 273 signed by President Johnson, that plan was reversed less than a week later. While the initial goal was to assist the people in South Vietnam, it was subtly added that assistance should be provided to defeat the communists. The war could be expanded to North Vietnam, and, as stated in the memorandum, higher officials should not even think about criticizing the new plan. ‘The first shots of that terrible war in Vietnam,’ as author Jim Marrs writes with a sense of drama, ‘were basically fired in Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas.’

The senseless war in Vietnam lasted about ten years. More than 58,000 Americans died, and 2,000 went missing. However, within the Department of Defense, the military, and the arms industry, there was little reason to complain. Nothing had come of all the cutbacks Kennedy had in mind; on the contrary, the military-industrial complex flourished as never before. As long as money can be made from misery, we will continue to see a lot of misery. But were individuals from this world really so greedy for money that they were willing to assassinate the president for it?

More on that another time.