American mafia: from street gang to national syndicate

The power of the underworld was exceptionally strong in the early sixties. Even more remarkable is the speed at which the power of the American mafia was acquired.

Around 1900, immigrants from all over the world entered the United States in search of prosperity, just as the Irishman Patrick Kennedy had set foot on American soil fifty years earlier. While the Kennedys succeeded, many other families continued to live in suburban poverty. People didn’t speak the language, lacked education, and couldn’t adapt to the customs of their new homeland. Street gangs, often consisting of young and ruthless criminals, emerged in the midst of this misery. America experienced the terror and intimidation of organized crime. Italians, Irish, and Japanese, notably, made their presence felt. The cunning protection racket, now familiar even in Amsterdam, was one of the frequently used crimes: businessmen were threatened, and then accomplices offered protection at high prices. Soon after, organized crime expanded, investing in gambling halls, narcotics, prostitution, and establishing strategic friendships with influential politicians.

From January 16, 1920, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution came into effect, still the only amendment ever completely repealed. For almost twenty-four years, the consumption of alcohol was prohibited in forty-six of the then forty-eight states. With the advent of Prohibition, the liquor trade moved to the illegal circuit, giving rise to a gigantic criminal empire. It was an era of mass illegal drinking, thanks to homemade concoctions or alcohol traded by the underworld. Profits were made from alcohol; the quality of, for example, a glass of whisky was four times worse than before, but the price skyrocketed from 15 to 75 cents in a short time. Bootleggers bought bottles of liquor for four dollars at sea, diluted the alcohol with water, and then sold four bottles for forty dollars each. Criminals became heroes of the street as suppliers of the prohibited good. Another equally worrisome development was the increasing involvement of honest businessmen in illicit activities. Joseph P. Kennedy was already quite wealthy, but the liquor trade made him even more prosperous (more on that in this article). He imported Canadian liquor into Boston and, after 1933 when the government finally realized Prohibition was not working, continued his business above ground with Somerset Importers.

Prohibition was a golden age for organized crime. In Chicago, Johnny Torrio was a feared man, succeeded by Al Capone after his early retirement. In New York, men like Frankie Yale and Arnold Rothstein were ambitious gangsters, but it was the families of Giuseppe Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano that made their mark. For the Masseria family, infamous men like Vito Genovese and Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano worked, the latter becoming the boss of bosses – il capo di tutti capi. Luciano ultimately realized a dream of earlier generations: he ensured that former enemies collaborated, forming a syndicate that stretched from the east to the west coast. Under Luciano’s leadership, not only traditional powers from Italy and Sicily but also men like Meyer Lansky, Dutch Schultz, and Benjamin ‘Bugsy’ Siegel gained more influence.

Prohibition had a significant impact on the rise of organized crime, but the moment Luciano collaborated with the U.S. government is also often cited in history books. On April 1, 1936, the criminal was charged with ninety counts of forced prostitution. Luciano was sentenced to thirty to fifty years in prison and confined to a notorious prison on the Canadian border. Difficult times awaited him until America became involved in World War II. In the first year of the war, 1942, the U.S. Navy faced problems. In March alone, twenty-four ships sank due to German actions. In a desperate attempt to turn the tide, they decided to turn to the mafia. Lieutenant Charles Haffenden met underworld figures like Joseph Lanza and Meyer Lansky at the Hotel Astor in New York. Lansky, a Jew, ensured that Luciano also came on board. American units were soon guided by Mafiosi in areas occupied by Germans, including the island of Sicily. ‘Operation Underworld,’ under the responsibility of the OSS, the precursor to the CIA, was a success. In gratitude, Luciano was transferred to a more lenient prison. On February 3, 1946, he became a free man – he was put on a boat to Sicily and never set foot on American soil again. U.S. authorities have always denied collaboration with the mafia.

In the early fifties, the issue of organized crime increasingly appeared on political agendas, although some prominent politicians and prosecutors still denied the existence of such syndicates. The most powerful denier was the director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover. A Senate committee chaired by Estes Kefauver investigated the circumstances, and for the first time, the ordinary American learned how professionally organized crime was within their own borders.

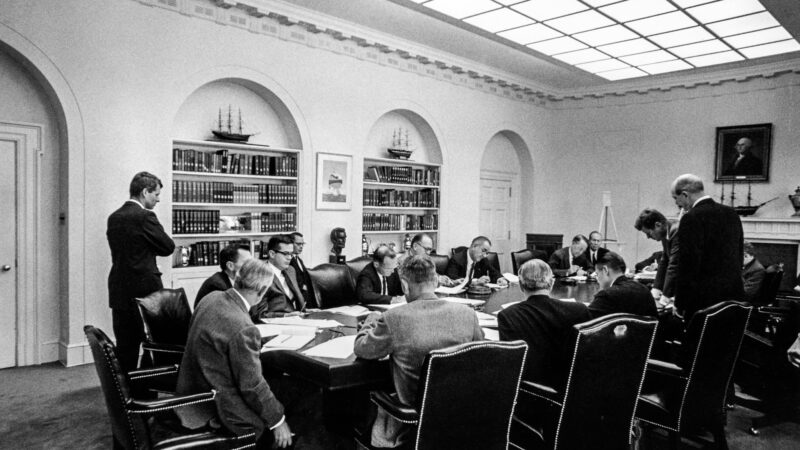

Near the small town of Apalachin, in the state of New York, a significant congress was organized on November 14, 1957, inviting all major mafia leaders. They came from all corners of the United States and almost all of them were apprehended thanks to an alert law enforcement officer. The public could watch the numerous interrogations that followed through the new mass medium, television. At that time, the young Robert F. Kennedy had already been a member of a new Senate committee, now chaired by John McClellan, for several months. He gained nationwide fame through his vigorous interrogations. Senator John F. Kennedy also served on this investigative committee, whose primary task was to examine how corruption had infiltrated militant labor unions, such as the truck drivers’ union. The leader of this union was the criminal Jimmy Hoffa. More on him another time.

The Kefauver Committee’s report exposed in the early fifties the extent of corruption: officials and law enforcement officers were extensively paid to favor criminals. Organized crime had by then expanded its influence. New markets were tapped into from New York and Chicago, reaching cities such as Kansas City, New Orleans, Tampa, and Dallas.