The FBI after the assassination

With the shots in Dallas, the most sensational murder investigation of the twentieth century began. The interrogations and the trial against Oswald were supposed to shed more light on the motives and the way in which Kennedy’s murder was planned. Oswald’s death two days later posed a problem for the new president. How could the case be best investigated, and by whom? President Johnson didn’t know on November 24, 1963, that he would also face another challenge. He was opposed by people who wanted the investigation conducted according to their own wishes and who did not favor an objective commission. This is the story of the FBI after the assassination.

Immediately after the murder, the FBI initiated a preliminary investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald. On Saturday morning, the bureau’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, called the new president (both in the above photo). Kennedy had been dead for less than twenty-four hours, and millions of Americans were still reeling from shock and confusion. It was 10 a.m. on November 23. All White House phone calls were recorded and preserved, but the recording of this call was later destroyed. However, there is still a transcript of the remarkable conversation, released in 1993. Among other things, Hoover told the president, “We have formally charged Lee Harvey Oswald with the murder of the president. However, the evidence we have at the moment is not very strong.” Johnson responded, “Do you have more information about Oswald’s visit to the Russian embassy in Mexico last September?” Hoover replied, “No. That is still a very confusing element at the moment. We have an audio clip and a photo of the man at the embassy who identified himself as Oswald. However, the photo and the sound on the tape do not match Oswald’s voice and appearance. In other words, it seems like there was a second person at that embassy. We also have a letter from Oswald that he sent to the Russian embassy in Washington, as you know, we read everything sent to that consulate—a very secret operation. But overall, we still do not have enough evidence for a conviction. Oswald continues to deny.” Johnson concluded, “I hope you can provide me with the results of your preliminary investigation soon. Keep me informed.”

The next day, Oswald was murdered. Two hours after nightclub owner Jack Ruby’s shot, Hoover called the White House again. “What concerns me the most,” he said to President Johnson, “is making a statement that can convince the public that Oswald is the real murderer.” On the same day, the FBI director called a close aide to the president, Walter Jenkins. Hoover had heard about a possible independent investigative commission. He told Jenkins that he was not happy about it. “Why don’t you let the FBI do it? We investigate the case and provide a comprehensive report to the Attorney General, Robert Kennedy. I’ve talked to his right-hand man, Nicholas Katzenbach, and he’s open to it. Both of us are eager to release something that will convince the public that Oswald is the only real culprit.”

Hoover was not lying about Katzenbach. In 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations released a memorandum from the Deputy Attorney General who stood in for grieving Bobby Kennedy. The text, written on November 25, 1963, to President Johnson’s aide Bill Moyers, is very remarkable: at no other time did a government representative speak so openly about the possibility of a conspiracy. Katzenbach wrote, “The public must be well informed. They must all agree that Oswald was the murderer, that he had no allies still at large, and that he would have been irrevocably convicted if it had gone to trial. There should be no room for speculation, such as the idea of a communist conspiracy behind the murder. In my opinion, we must have the FBI conduct a thorough investigation of Oswald and the murder as soon as possible. The results of the investigation may contradict what the Dallas police declare, but the FBI’s good image will give our investigation enough authority. We need to act now to preempt speculation in the country.”

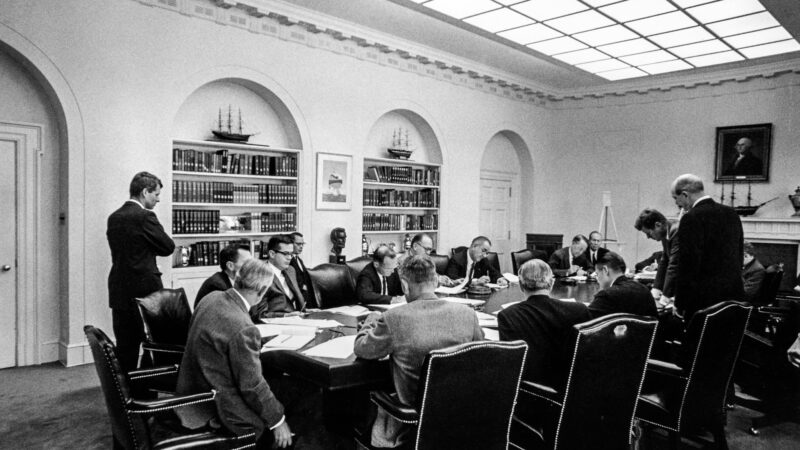

Like Hoover, President Johnson was originally against a commission. In a phone call on that same November 25, he told Hoover, “President Herbert Hoover tried it a long time ago, such an investigative commission. Such an untrained team often does more harm than good. It would be a circus, with a lot of media attention.” Apparently, the pressure for the commission was too great. On November 29, the president called the FBI director again, and this time he informed him that the FBI’s preliminary investigation would indeed be thoroughly reviewed by a task force including Senators, representatives, and others. Hoover resisted, but the president told him there was no turning back. The two continued their conversation by going through some candidates for the commission and discussing various details of the murder in Dallas.

From this point on, the president worked on forming the commission, which would be chaired by Earl Warren. Later that same day, he called Senator Richard Russel, the conversation in which Lyndon B. Johnson said, among other things, “It won’t take us much effort. All we have to do is evaluate a report from Hoover, a report that’s already been made.” Hoover was personally pleased with the appointment of Gerald Ford, the fifty-year-old representative from Michigan who would become president ten years later. The director wrote in one of his internal memos that he expected Ford to represent the interests of the FBI in the commission. And so it happened: throughout the entire investigation, he maintained close contacts with the FBI and kept Hoover informed as a loyal informant about what was discussed behind closed doors.

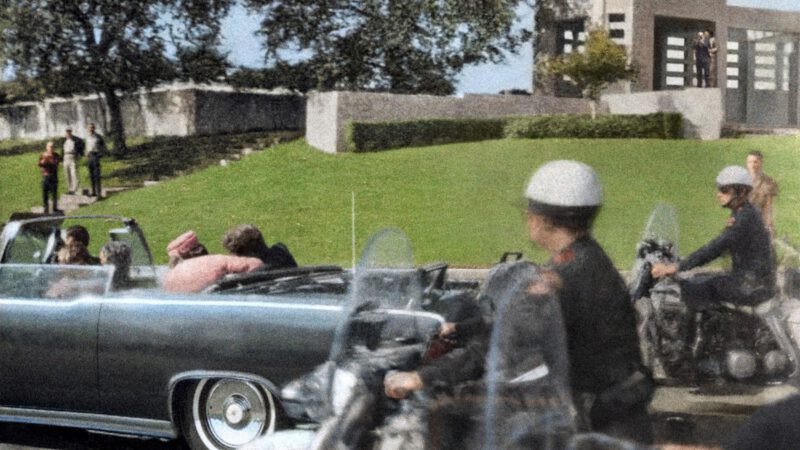

The FBI played a significant role in the investigation that took place immediately after the murder. The bureau was the first official entity to complete an investigation. On December 9, 1963, only seventeen days after JFK’s murder, the Warren Commission received the FBI’s report. A rushed job, as FBI employees would declare many years later. In the months that followed, the FBI remained the primary source of investigation for Earl Warren and his people. The main discrepancy between the FBI’s reports and the Warren Commission was in the fired bullets. Both times it was concluded that three shots were fired at Dealey Plaza. According to the FBI, the first bullet hit Kennedy, the second hit Governor Connally, and the third bullet was fatal, piercing the president’s head. However, the Warren Commission drew different conclusions about the first two bullets. The commission could not ignore the slightly injured James Tague. According to the commission, the first bullet hit this bystander at the overpass, and the second bullet went through both Kennedy’s and Connally’s bodies—the so-called single-bullet theory. The third bullet hit Kennedy in the head.

In the 1970s, other commissions that conducted extensive reexaminations concluded that the FBI’s investigation into Kennedy’s murder had been seriously lacking. Too little attention had been paid to other possibilities than the theory that only Oswald was the perpetrator. Additionally, the FBI shared crucial information with other agencies sparingly. But those are stories for another time.

2 thoughts on “The FBI after the assassination”