Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union

In September 1959, Lee Harvey Oswald left his homeland. His destination: Moscow, in the heart of the Soviet Union, at the height of the Cold War. An article on Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union.

The steamship Marion Lykers carried only four people to Le Havre. There was little contact between Oswald and the other three passengers. They had no inkling of the travel plans of the nineteen-year-old boy, whom they did not find sympathetic. On October 8, the ship docked in the French port city, and on the same day, Oswald traveled to Great Britain, where he arrived a day later. In Southampton, he told officials that he wanted to stay for a week before heading to Switzerland, but in reality, he flew to Helsinki on the same day. It was a public secret that nowhere else in the world could a visa for the communist world be obtained as quickly and easily as in the Finnish capital. On October 15, he then took a train to Moscow, a journey of a day.

After a total of twenty-seven days of travel, Oswald finally reached his destination. The adventures of Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union began. In the Russian capital, he was met by a young woman from the travel organization, Rima Shirakova. Oswald immediately confided in this girl that he did not intend to leave quickly; he wanted to turn his back on his homeland and apply for Russian citizenship. In the diary later found among Oswald’s belongings, it described how Rima reacted: speechless but immediately willing to help. On October 18, Oswald’s twentieth birthday, she gave him a book by Dostoevsky with a note: ‘May all your dreams come true!’ Meanwhile, various parties were already aware of his request to change nationality, and even the Russian intelligence service, the KGB, was particularly interested. Did this ex-marine speak the truth, and could they use him with all his knowledge of spy planes, or was he working for the enemy intelligence service, the CIA? Oswald was questioned shortly thereafter but remained tight-lipped.

On October 21, he received the message that his visa was about to expire; he had to leave Russia within two hours. However, Oswald managed to prevent that: he cut his left wrist, and Rima found him, heavily bleeding and unconscious, in the bathtub of his hotel room. It was considered a cry for attention, an effective method to make it clear that he was serious. The false suicide attempt worked, and at the end of October, he was discharged from the hospital. He then informed the U.S. embassy on October 31, telling Consul Richard Snyder and his assistant John McVickar that they could keep his passport. He wanted to renounce his U.S. citizenship as soon as possible. From this moment on, Oswald was closely monitored from his homeland. Both the FBI and the CIA had an Oswald dossier from the fall of 1959.

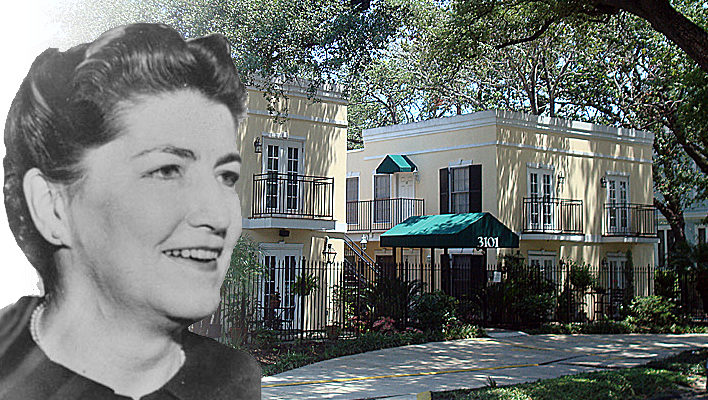

His family in the United States was by now aware of all the developments. Marguerite wanted to call, but Oswald did not allow a phone conversation. However, he wrote to his brother Robert, expressing the wish for his choice to be respected. They should not try to lecture him. Meanwhile, he continued to wait for the decisive message from the Russian authorities. Oswald really did not want to leave the country anymore. He allowed American interviewers, Aline Mosby of United Press International (UPI) and Priscilla Johnson McMillan of North American News Alliance (NANA), to interview him, the first non-Russian media Oswald gave permission to. The United States was highly interested in this man and his intentions to defect. For the rest of the year 1959, Oswald rarely left his hotel room and was mainly occupied with his study of Russian.

On January 4, 1960, all uncertainty came to an end. Oswald did not obtain Russian citizenship but became stateless. Additionally, he was banished by the Moscow authorities to the distant Minsk, the current capital of Belarus. In that distant provincial city, it was thought that he could pose little danger. Oswald hated that he still did not become a real Russian, but he was relieved that he no longer had to live in uncertainty. On January 7, he arrived in Minsk, starting a new chapter in his life. Oswald described his early days in Minsk as a ‘Russian dream.’ He was assigned a spacious apartment for a minimal monthly amount and got a job at an electronics factory in the city center, where he earned much more than the average Minsk resident. Defectors were well taken care of. Oswald made friends, was popular with the girls, found his work not boring, and was an interesting subject for many Russians curious about life in wealthy America. In the summer, he went hunting in the woods, and he fell in love with his colleague Ella German from the first moment. Due to the poverty he saw around him, he began to doubt communism for the first time in his life. Throughout these months, Oswald was constantly observed by the KGB.

The first real setback came in the last month of 1960. Ella German responded negatively to his marriage proposal, and that blow hit Oswald hard. A year after the start of his statelessness, in early 1961, he wrote depressing words in his diary. He was going through a tough time. He doubted whether he had made the right decision to emigrate to the enemy. ‘The work is bad, I can’t spend money anywhere, there are no nightclubs or bowling alleys, just absolutely no recreation apart from dance evenings.’ In response to a letter from Moscow asking if he still wanted Russian citizenship, Oswald responded negatively. However, he wanted his statelessness to be extended by a year. In February, Oswald wrote again to Moscow: he wanted his passport back and an exit visa to the United States. His homeland, where John F. Kennedy had become the new president in the meantime. Perhaps the new wind in the United States stirred a lot in the young man so far from home.

Oswald feared the consequences: he was afraid that he would be prosecuted once he set foot on American soil. Collaborating with the enemy would not be appreciated. Nevertheless, he decided to take the risk gladly. The letter marked the beginning of a sixteen-month correspondence with the authorities. And then Oswald received another unpleasant message from his homeland: the navy had learned of his defection to the Soviet Union and had decided to change his honorable discharge to the negative status of undesirable discharge, a dishonorable discharge. From a commendable ex-marine, he suddenly became an unwanted soldier, deemed unfit for service in the Marine Corps. His good name was seriously tarnished.

The return to the United States became even more complicated when Oswald, during a dance in March 1961, met a Russian girl, Marina Prusakova (1941), whom he married on April 30, 1961. After the marriage, Oswald cautiously re-established contact with his family: on May 5, he sent a letter to his brother Robert, and on June 1, a letter to his mother. Meanwhile, the KGB continued to observe them. Oswald was even eavesdropped on in his own apartment, as revealed after the fall of the Berlin Wall when the KGB became more liberal with the release of documents. Norman Mailer reported on this in his book “Oswald’s Tale,” for which he received the Pulitzer Prize. Thanks to eavesdropping equipment and transcripts of everything that happened in Oswald’s apartment, we know that the relationship between Oswald and his wife was already under pressure in the summer months of 1961. Marina increasingly expressed her doubts about her husband and the trip to the U.S. The happy weeks of marriage were over; it was a time full of tensions. But there was also some luck: Marina turned out to be pregnant. And later that year, she got her Russian exit visa, bringing the trip to the United States very close for the couple.

Marina gave birth to a daughter, June, in March 1962. It was already a problem at the height of the Cold War to grant Oswald permission to return, but it seemed even more impossible to allow his Russian wife and child to depart. Remarkably, Oswald managed it all. On May 22, the family left Minsk for a trip to Moscow, where much still needed to be arranged. The embassy provided tickets for the SS Maasdam IV, a ship that would depart from Rotterdam to Hoboken, New Jersey on June 4. The tickets cost $418, an amount borrowed to the Oswalds by the embassy. The train journey to Rotterdam was also paid for by the embassy, making the total loan to the U.S. government $435.71. On June 1, the stay in Moscow came to an end. The train departed at 4:10 PM via the familiar Minsk to the Netherlands: eighteen months after Lee Harvey Oswald first officially expressed his desire to return home. And that was the end of Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union.

- More on the years of his youth, check this article on Oswald

- More on his time on the SS Maasdam, check this article

- Learn more on Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union in this documentary

2 thoughts on “Lee Harvey Oswald in the Soviet Union”