President John F. Kennedy: his thousand days

Father Joseph Kennedy saw his greatest wish come true. He himself had not succeeded in reaching the White House, let alone getting close to it, but his son was elected as the president of the United States on November 8, 1960. President John F. Kennedy was the 35th president of his country.

He became the first Catholic president, the first Irishman in the White House, and at the age of 43, the youngest president ever; he was the first leader of the country born in the twentieth century. On January 20, 1961, he was sworn in by Chief Justice Earl Warren. Kennedy’s inaugural address began at 12:51 local time. It lasted only 14 minutes, comprised 1364 words, and would go down in history as one of the best ever – written by Kennedy and his top speechwriters and loyal assistants such as Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Theodore Sorensen. A speech full of promises and a touch of optimism and confidence. In the conclusion, Americans and other global citizens were addressed with their own responsibility in the famous lines: ‘And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.’ A new face, a new sound: a new era had begun. As Kennedy said in his speech: ‘Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans – born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage – and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed.’

The presidency of John F. Kennedy: key events

Exciting years were ahead, both domestically and internationally. Kennedy was well aware that these were not easy times: ‘Within eleven weeks, I was made Senator to President, and in that short time, I inherited Laos, Cuba, Berlin, the nuclear threat, and the rest.’ While various internal social and economic issues were at play, the period under Kennedy was primarily focused on foreign policy.

In the US

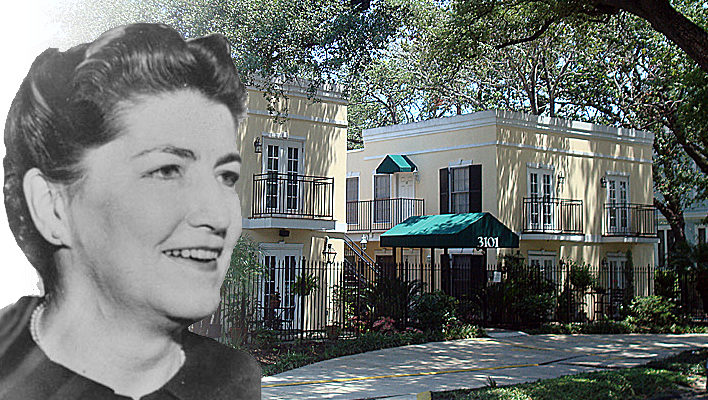

Within the national borders, Kennedy was extremely conservative. He named his policy the ‘New Frontier,’ a term he introduced in his speech at the Democratic Convention in the summer of 1960. With it, he wanted to express that the United States, after a period of stagnation under Eisenhower, needed to be set in motion again: exploring new frontiers together. In the field of domestic politics, he proposed various social measures, such as medical care for the elderly, federal support for education, and addressing urban problems. However, due to opposition from Congress, he failed to implement his main reforms. Additionally, he faced the intensification of the racial issue. The civil rights of the black population would play a significant role during Kennedy’s years in the White House.

Especially in the South, there was still a great deal of racism. Being required to sit at the back of the bus for people with dark skin was just one example among many. Racial segregation had not long ago been a huge issue within American society. Resistance to it increased, with Reverend Martin Luther King as an inspiring leader. Sit-ins at lunch establishments followed, and hundreds of large demonstrations were held across the country. The president initially reacted very hesitantly. He knew that a lenient attitude toward blacks risked losing the favor of millions of white voters in the South. Although John F. Kennedy spoke inspiring words, he only intervened in alarming events – more often, he left regulations to the individual, often too conservative states. To the dissatisfaction of King, who blew off steam in the national press: ‘The president has proposed a ten-year plan to put a man on the moon, but we don’t even have such a plan to elect a Negro to the state parliament of Alabama.’ Kennedy later made up for his hesitating stance. Especially in the last year of his life, he strongly demonstrated that he wanted to definitively eradicate discrimination. A speech on the admission of black students to a university in the same state of Alabama was one of the best during his presidency. And Kennedy offered his services when Martin Luther King wanted to organize his famous march in Washington DC in August 1963 – the demonstration that ended with the ‘I have a dream’ speech.

In addition to a tentative approach to tackling racism, JFK’s government was also the first to want to end the growing problems of organized crime. Never before had mafia bosses suffered as much as in the 1037 days when JFK was in charge. Arrests and parliamentary inquiries followed: the influential mafia world was no longer ignored.

Foreign policy

However, Kennedy’s main interest was in foreign policy. Here, he showed himself to be a pragmatic leader. He presented himself as an idealist: global backwardness and injustice had to be combated. To achieve this, he established volunteer organizations such as the Peace Corps and the Alliance for Progress. The Peace Corps still stands as the most successful program in the history of American foreign policy.

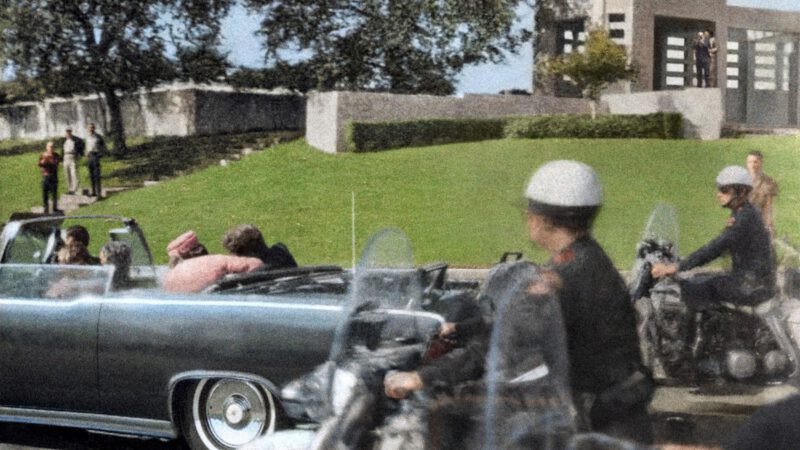

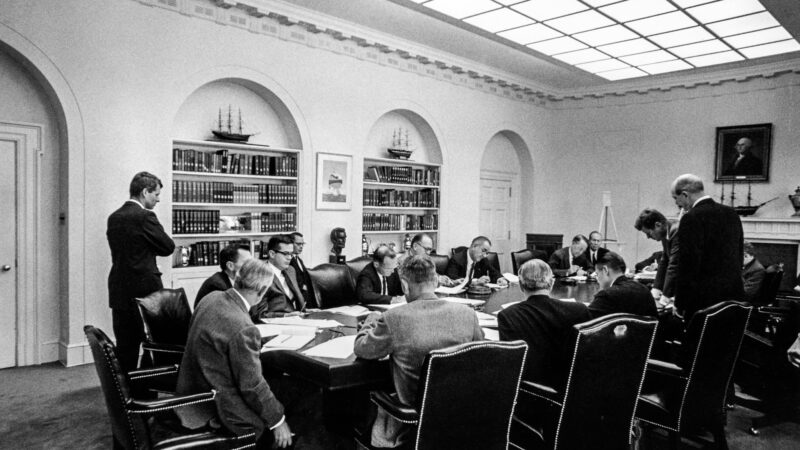

Kennedy took office at the height of the Cold War. The United States and the then Soviet Union were at loggerheads. Kennedy was particularly focused on collaboration, on ending tensions. Oddly enough, he had been one of the biggest advocates of the Cold War among all Senators. The president now called on the Soviet Union to engage in talks on arms control but also on cooperation in science and space exploration. JFK had been president for only a few months when he was confronted with a legacy from his predecessor: the planned invasion of Cuba by counter-revolutionaries who still had a score to settle with the leader there, Fidel Castro. The red threat raged worldwide, but ironically, the tension was highest on an island just 144 kilometers from the American coast. The Bay of Pigs invasion was led by the CIA. It turned into a fiasco for the United States, partly due to Kennedy’s overly cautious policy. Some high-ranking CIA directors were sacrificed by the president, but Kennedy was responsible and had failed tremendously in those days of April.

He did much better a year and a half later, in October 1962, when it almost led to a (nuclear) war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Sunday, October 28, proved to be a turning point in the crisis when it was announced that the Soviet Union would comply with the demands of the U.S., and the ships with nuclear warheads would turn back. In conservative American circles, Kennedy was hated for the concessions, but the president had averted a possible nuclear war with his diplomacy. It would remain his greatest achievement, Kennedy’s finest hour. The New Yorker spoke of ‘perhaps the greatest diplomatic victory of any president in our history.’ There were also critical voices: Kennedy saved the world, but perhaps with less aggressive obsession against Cuba and Castro, it never would have come to this.

The success of the Cuban Missile Crisis paid off. Nine days later, the Democrats won four seats in the Senate (Edward Kennedy was one of the newcomers) in the midterm elections, and only four seats were lost in the House of Representatives. The best result for a party since the midterm elections of 1934, during Roosevelt’s first term. Politicians who criticized Kennedy for his soft policy for months were now mercilessly punished. And Kennedy emphasized in his best speech, on June 10, 1963, in Washington DC, that he had no intention of deviating from his policy. ‘We must work for peace. For everyone. Not only in our time, but forever. We cannot simply set aside our differences, but let us at least ensure that there is room for diversity in our world. Ultimately, we all inhabit the same small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish the future of our children. And we are all mortal.’

Another highlight for Kennedy was, sixteen days after his peace speech, his visit to Berlin. Two years earlier, Khrushchev had set up a barbed wire fence along the 43-kilometer border between East and West Berlin, which was later replaced by a concrete wall. Now, the American president expressed his solidarity with the words: ‘Ich bin ein Berliner.’ It was a great morale booster for the West Berliners, who lived in an enclave deep in East Germany and feared an East German occupation. On Rudolph-Wilde-Platz, the square that would be named after him after his death, the president addressed 150,000 ecstatic people.

Things were less successful in Vietnam. Eisenhower had sent a few dozen military personnel to this country – at Kennedy’s death, there were almost seventeen thousand. Under the young president, there was an escalation of an American terror campaign against the Vietnamese people. The conflict, stemming from deep-seated fear of communism, became a struggle for America on both the real front and the home front.

Kennedy did not have it easy in the early sixties. Fortunately, he was not alone. One of his first tasks after the election in November 1960 was the formation of his cabinet. More on that soon.

Links:

President Kennedy: more on his youth, the path to the White House.

John F. Kennedy: more on the key events

One thought on “President John F. Kennedy: his thousand days”