The rise of J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI

Much has been written about the origin of the FBI, its growing influence and the rise of J. Edgar Hoover. Who was this director, and why did he adopt such an uncooperative stance after Kennedy’s assassination? Did the bureau do enough to prevent Kennedy’s murder? Despite numerous investigations, many questions remain unanswered even fifty years later.

The birth of the federal bureau

In the early 20th century, Charles Joseph Bonaparte, a grandson of Napoleon Bonaparte’s youngest brother, served as the U.S. Attorney General. He actively advocated for national reforms and recognized the need for significant improvements in federal-level investigations. The U.S. Congress agreed with him, and on May 27, 1908, they passed a law implementing Bonaparte’s plan, supported by then-President Theodore Roosevelt. A special unit was established, comprising its own special agents. Initially named the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), it was led by Stanley W. Finch, the first director.

The primary task at the Bureau’s inception was to investigate crimes that crossed state borders. By 1910, its jurisdiction expanded. Due to new laws and the First World War, the BOI’s workload increased. The bureau grew with over 300 new special agents and 300 additional support staff. Smaller offices were established nationwide, led by a special agent reporting directly to Washington. The BOI became responsible for espionage and sabotage, assisting the Department of Labor in investigating hostile foreigners. During this period, the number of special agents with general investigative skills and proficiency in foreign languages increased. Due to limited powers, employees had to be creative in handling cases of national urgency falling under local jurisdiction. For example, during the peak of the gangster era (1921-1933), Al Capone was investigated as a “fleeing federal witness.” The bureau gained high status through creative investigative approaches.

After Director Finch, Bielaski, Allen, and Flynn successively led the young organization. When William J. Burns became the bureau director in 1921, he appointed the then twenty-six-year-old John Edgar Hoover as his assistant. Hoover had only been with the bureau for four years but had already achieved a high status. He led operations related to hostile foreigners during World War I and assisted the General Intelligence Division in investigating suspicious anarchists and communists. On May 10, 1924, Attorney General Harlan F. Stone appointed the young Hoover as the interim director of the Bureau of Investigation. Hoover held this powerful position for an unprecedented 48 years until his death in 1972, serving eight presidents and over a dozen attorneys general. His life seemed filled with intrigues, controversies, and scandals, depicted in Hollywood productions, with the latest in 2011 featuring Leonardo DiCaprio.

When Hoover was definitively appointed director twenty days before his thirtieth birthday, the BOI had around 640 unarmed employees, including approximately 440 special agents working in branches across various cities. The organization would undergo drastic changes under Hoover. The number of offices continued to expand, and Hoover professionalized the organization significantly. Strict personnel policies, an official training center, a handbook for each employee, and new departments like a technical laboratory and the Identification Division, where national personal files were compiled, were introduced.

On July 1, 1932, the name Bureau of Investigation was changed to United States Bureau of Investigation (USBOI), and in 1935, it became the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The FBI was born, and under Hoover and his team, it became busy. World War II was on the horizon. Hoover’s success fluctuated. He often impressed but also made questionable decisions. In 1941, he made the biggest mistake of his life by ignoring clear signals from double agent Dusko Popov about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, four months before the national tragedy in December 1941. He also failed to alert Roosevelt. Edwin Layton, who conducted an in-depth study of the attack, stated, “Hoover completely missed the mark. His failure was a gigantic blunder on the road to Pearl Harbor.” William Casey, CIA director in the 1980s, remarked, “Hoover had shown early on his utter incompetence to lead a service in wartime. The way he handled the Popov case could have been an indication of his later legendary reluctance and his overly simplistic thinking.”

During this time, various U.S. intelligence agencies were increasingly centrally controlled, and they began collaborating more. While the FBI conducted work within the country, there was a need to gather intelligence beyond its borders. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) emerged, the precursor to the CIA. The intelligence agency, as mentioned in chapter 4, was the brainchild of the experienced William Donovan, a general who was always a rival to Hoover. The director would have preferred the foreign activities to fall under the FBI’s purview wherever possible. Hoover obstructed wherever he could. He was furious about the establishment of the CIA and ordered his staff not to share information with “the enemy.” Donovan later commented, “The German intelligence service received more cooperation from the FBI than we did.” The feud with the CIA would persist until his death.

Although foreign responsibilities had eluded Hoover, the FBI headquarters remained busy even after the war. The growing communist group was seen as a threat to the state, and crime was still rampant. By the end of 1943, the staff had increased to 13,000 employees. The significant increase was necessary to support all the new functions of the FBI. Due to the expanding jurisdiction, the anti-communist hysteria during the Cold War, and Hoover’s chosen new enemies such as progressives, the Church, the media, and civil rights activists, there was plenty of work for the bureau, even in the post-war years.

In historical perception, the ‘bulldog’ – Hoover’s nose was hit by a baseball in his youth – does not hold a favorable place. He is characterized as a threat to democracy, a man who abused his power in unprecedented ways. “Illegal activities were so ingrained in the FBI’s policies that top officials still didn’t know how to conduct an investigation without breaking the law years after Hoover’s death,” wrote Tim Weiner in “Enemies: A History Of The FBI,” the sequel to his well-received book on the history of the CIA.

His primary weapon was knowledge. Washington feared the damage that the master blackmailer Hoover could inflict. Ironically, despite all the incriminating information now available, the FBI headquarters in the capital still bears his name, as if nothing happened. John O’Brian was a significant figure on the bureau in its early years, a man who, as Hoover’s boss, was partially responsible for paving the way for the talented and ambitious man. Asked about his role in advancing Hoover’s career just before his death, he said, “I prefer not to talk about that out loud. That is a sin for which I will have to atone.”

48 Years of absolute power: the rise of J. Edgar Hoover

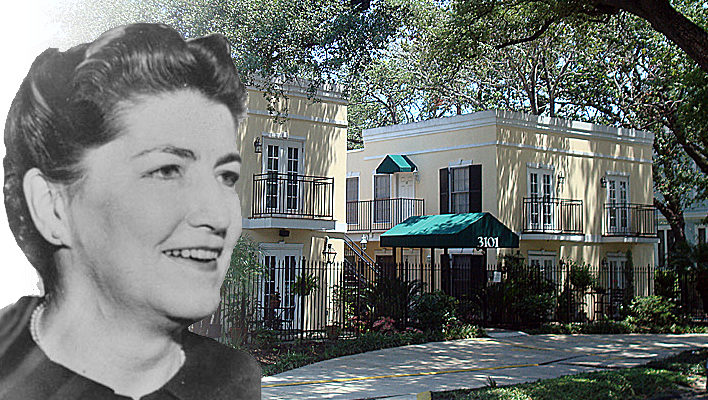

John Edgar Hoover (good biography here) was born on January 1, 1895, in Washington, DC. He lived there his entire life, in the family home until 1938 and then in his own residence after his mother’s death – he was already well past forty. At a young age, he kept a dossier on his own life, and at thirteen, he began a diary in which he detailed everything that came his way. In 1917, he graduated from George Washington University with a law degree, and on July 26 of that year, he began his career at the investigative bureau. His initial responsibilities included gathering evidence against revolutionary and extremely radical groups and creating a massive card system on leftist individuals. He became the head of a new department, and surprisingly, at the age of twenty-four, he excelled in the role. The rise of J. Edgar Hoover had begun. As he advanced in his career, his legend grew. In 1924, he became the director of the FBI. There were periods when not a day passed without Hoover being quoted in national newspapers. Operating like a true dictator, Hoover built an empire of his organization – aided by his organizational talent, a keen sense of the country’s mood, and an unmatched ability to promote himself. Hoover was loved by the people, a remarkable achievement considering the many scandals surrounding the director.

Smearing political enemies by spreading rumors was a method Hoover frequently used to abuse his power. They were shadowed until compromising material was available. For friends, Hoover was much kinder. The vast FBI archive was not accessible to unauthorized individuals, but when it suited him, the director gladly made an exception. Friendly journalists and politicians gladly took advantage of this. In 1948, Hoover hoped that Thomas Dewey would be elected president, and to help him, he made all FBI sources available. Opponents of Truman could smear the president a few years later, thanks to an afternoon in the FBI archive. Later on, Hoover welcomed Vice President Richard Nixon – he could use some information for his attack on a political opponent in California. These practices made J. Edgar Hoover a powerful man. He not only collected information but also controlled it. According to an official count, the Bureau possessed 883 files on Senators and 722 on Congress members after Hoover’s death. Some are still withheld, while others have been destroyed.

The eavesdropping scandal at the Watergate Hotel in 1974 cost Nixon his position. It would later be discovered that Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson were all guilty of eavesdropping and shadow activities unrelated to domestic security or crime. These political activities had political goals, and the means were provided in all cases by the FBI. By ignoring ethics and the law and using the FBI for these purposes, they all became indebted to Hoover. The FBI director had to be kept in good favor. “His knowledge made him as valuable to his friends as dangerous to his enemies,” President Nixon would say after his forced resignation in 1974. Most Americans saw only the formidable propaganda machine and the impressive corps of agents, but insiders knew Hoover’s dark side. Truman, a month after taking office in 1945, said, “We don’t want a Gestapo or secret police. The FBI tends in that direction. They mess around in sex scandals and outright blackmail when they should be catching criminals. They also have a way of mocking local law enforcement. This has to stop. What we need is cooperation.” Journalist Tom Wicker of The New York Times wrote critically about the American people, “Hoover was in power for an enormous length of time and abused his position. But the American people enjoyed it. They swallowed all the propaganda eagerly and were devoted to Hoover until his death. No one protested when he, the guardian of our freedom, hunted harmless communists. No one contradicted him when he called Martin Luther King a liar. Publishers gladly published his moralistic stories for the eager public. If Hoover did indeed cross so many boundaries, it happened for an audience that watched happily and gratefully.”

In his early years, the ambitious Hoover developed a deep hatred for communism. That population group became his greatest enemy. In the United States, opinions were divided on the actual threat, but Hoover was clear: every communist should be considered a state enemy and should, therefore, be deported. In a speech to congressmen in 1947, “Communism is spread by devilish machinations of dark figures engaged in un-American activities.” Hoover managed to gather a large number of supporters in his life’s work. A still unknown, young Congressman immediately offered his cooperation, the beginning of a lifelong good relationship between Hoover and Richard Nixon. When the Republican later became president, Hoover was a regular dinner guest at the White House. And when Hoover died on May 2, 1972, Nixon arranged a state funeral. Author Jim Marrs suggests in his book “Crossfire,” “Nixon always made extensive use of Hoover when he needed him in emergencies. When Hoover died, Nixon had to deal with it alone – and soon he drowned in the Watergate scandal. That tragedy would never have happened if Hoover were still around. He would have arranged something. Hoover would have weathered that storm.”

Nixon was not the only future president who sided with Hoover early on. A talented actor named Ronald Reagan, at the director’s urging, collected information about communists in the film industry. Every prominent member of the leftist cultural sector was mistrusted. The FBI dossier on the alleged state-dangerous communist Charlie Chaplin counted 1900 pages; in 1952, the comedian was banned from the country. Americans were terrified of a (nuclear) war with the Soviet Union, so Hoover got away with his fight against communists. He even became a national hero. Side by side with Senator and renowned communist hunter Joseph McCarthy, the FBI director used tax dollars on an unprecedented scale for a years-long crusade that ultimately resulted in the discovery of only four truly dangerous communists.

The hunt for communists is just one example from a long career full of madness. When Hoover was on a diet for a while, every employee had to follow his example. Bureau heads now had the task of closely monitoring their employees’ weight, and dismissal followed if someone was too heavy according to the boss’s new, absurd standards. Meanwhile, Hoover lived at the expense of the taxpayer. His house and garden were perfectly maintained by FBI employees, and he declared his holiday trips, delicacies from all corners of the U.S., shamelessly flown in at the community’s expense. The list of objectionable elements from Hoover’s long career is long, very long. However, Hoover is most guilty of what investigators call his most serious dereliction of duty.

We’ll save that for another time.

Links:

Was J. Edgar Hoover blackmailable?

The FBI after the assassination

One thought on “The rise of J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI”