Kennedy’s youth: the man before he became the President

An article on Kennedy’s youth. John F. Kennedy was born on May 29, 1917, as second son of Joseph P. Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald. HIs brother Joseph Jr. was two years older. He lived with his family in Brookline, near Boston, until 1927. Afterward, the growing family moved to the upscale suburbs of New York City. Between 1918 and 1924, four girls were born after him, one of whom had a mental disability. Subsequently, Robert Fitzgerald ‘Bobby’ Kennedy (1925-1968), Jean Ann Kennedy (1928-2020), and Edward Moore ‘Ted’ Kennedy (1932-2009) followed. The family spent summers in Hyannis Port, a village on Cape Cod peninsula, south of Boston, where they had a residence of 24,000 square meters with several large houses. Christmas and Easter were always celebrated in a different vacation home in Palm Beach, Florida.

In addition to his privileged background, John F. Kennedy – known as Jack to his close friends – demonstrated intelligence, achieving good academic results. Jack attended Harvard after high school, where he focused on sports and social life. In 1937, he traveled with his friend Lem Billings through France, Italy, Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands, ending the journey in England (nice article on this summer). In March 1939, he returned to the United Kingdom, studying in London. Two months later, he traveled through Europe again, reaching Moscow and Jerusalem, among other places, to gather information for the thesis he had to write a year later. This dissertation, discussing why England was unprepared for the war, became a bestseller. Some claimed later that renowned journalists had contributed significantly, and that after publication, father Joe bought large quantities of it. Regardless, Jack graduated with honors in international relations.

The only dark clouds lingering over his life were his significant health problems. Throughout his life, he faced mysterious ailments and stared death in the face several times. The fact that John F. Kennedy suffered from Addison’s disease and lived with severe back pain since childhood, with predictions from friendly doctors that he wouldn’t live long, was carefully kept out of the media. Whenever a camera appeared in the distance, the crutches were handed over to a family employee. A son of Joseph P. Kennedy couldn’t appear helpless. Image is everything, Joe knew: ‘It doesn’t matter what you really are; all that matters is what people think you are.’

Jack rarely complained, as his friends later attested. Acknowledging Kennedy’s likely suffering, his achievements during the war earned him much respect, although some events might have been exaggerated. According to the most famous anecdote, in August 1943, he supposedly saved his crew after their torpedo boat was rammed. Lieutenant Kennedy allegedly swam for five hours, reaching an island with his severely wounded colleague Pappy McMahon in tow. Historians doubt the true heroism of the event, but Kennedy received a high honor for it in his home country. Despite not considering himself a hero, the family’s publicity machine went into full swing. Kennedy’s active duty lasted six months.

In August 1945, James Forrestal, the Secretary of the Navy and a friend of father Joe, took twenty-eight-year-old John F. Kennedy to Germany. Forrestal, a former banker, belonged to a small elite of Americans engaged in trade with Germany since 1920. Other notable figures in this group included Prescott Bush, father and grandfather of future presidents, and John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State under Eisenhower and brother of Allen Dulles, later dismissed by Kennedy as the CIA director. Initially, they did not see Hitler as a threat, supporting the controversial views of Ambassador Joe Kennedy. Despite these authoritative opinions, young Kennedy developed his own perspective. He kept a detailed diary, expressing his thoughts on policy between the lines and documenting visits to Hitler’s bunker, General Eisenhower’s headquarters in Frankfurt, and the Eagle’s Nest in Southern Germany. The trip was intended as an internship to provide Kennedy with insights into the policy during World War II, gradually preparing him for a political career. Although he initially wanted to be a journalist, he decided not to disappoint his father after the death of his older brother. Kennedy later stated, ‘It was as if I were drafted into the army. My father wanted his eldest son to go into politics. “Wanted” is not the right term – he more or less demanded it.’

Shortly after the war, JFK represented Massachusetts in the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. The Democrat was only 29 years old and had transformed from a soldier to a statesman in a short time, with the help of his father and his grandfather, the former mayor of Boston. Their power, money, PR skills, and political experience were valuable, but Kennedy also secured the seat through the many hours he invested in his campaign. His appearance also played a role: Jack was particularly adept at attracting female voters. In 1946, the Junior Chamber of Commerce named Kennedy the most outstanding man of his generation. However, there were dark moments in his life; he continued to struggle with significant health problems, and in 1950, his grandfather, Honey Fitz, whom Kennedy admired, passed away. The admiration was mutual, as the two shared many similarities: humor, charisma, and ambitions. John F. Kennedy inherited these traits from his family, coupled with his father Joe Kennedy’s money and ruthless approach; there was no reason to doubt this young Kennedy’s success in politics in the early 1950s.

During the next five years, Kennedy achieved little in the predominantly Republican House of Representatives. He traveled extensively around the world, visiting every city and town in his state, Massachusetts, preparing for his next step: a seat in the Senate. Father Joe financed the campaign again, but the campaign manager was now his twenty-six-year-old brother, Robert. He led a team of about 25,000 people. For the first time, television was used, in addition to radio, in the battle for voters. Kennedy captivated every demographic: black Americans, Jews, Irish (naturally), Italians, and the French. However, he achieved the most success once again with female voters. Despite the family’s constant financial support, Kennedy narrowly won the election on November 4, 1952. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected as the new president that month, succeeding Democrat Harry S. Truman. The new governor of Massachusetts was also a Republican. Kennedy’s victory as a Senator in the face of this Republican wave was a significant achievement.

Not long after his election, he wrote his acclaimed book “Profiles in Courage,” about Senators with views differing from their party. Later, skepticism arose about this achievement: his right-hand man Theodore Sorensen was said to have not only done the research and editing but also served as a ghostwriter. Sorensen, who later co-wrote important speeches such as the inaugural address and the speech in which Kennedy announced the race to the moon, always denied this. Kennedy won a Pulitzer Prize for the publication, thanks to efforts by his father – his friend Arthur Krock was on the jury. Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of former President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a heavyweight in the Democratic Party, commented significantly later: ‘That young Kennedy should show a little less profile and a little more courage.’

In 1956, Eisenhower’s first term in the White House ended. Adlai Stevenson was nominated by the Democrats to challenge the wartime commander-in-chief. It had almost been John F. Kennedy as his running mate, the potential new vice president. Kennedy narrowly lost that battle to Estes Kefauver, but the 1956 Democratic Convention gave him national recognition, more than he had achieved in ten years of politics. Kennedy’s good looks and speeches stood out and immediately made him the candidate for the 1960 elections. However, Stevenson and Kefauver did not win the 1956 elections; Eisenhower (and his vice president Richard Nixon) were re-elected. Kennedy, in turn, was easily re-elected to the Senate in 1958. This time, his youngest brother, Edward Kennedy, organized the campaign.

Meanwhile, Jack’s health deteriorated more and more. Between 1955 and 1957, he was hospitalized nine times. It was professionally concealed, but the politician even had trouble tying his own shoelaces.

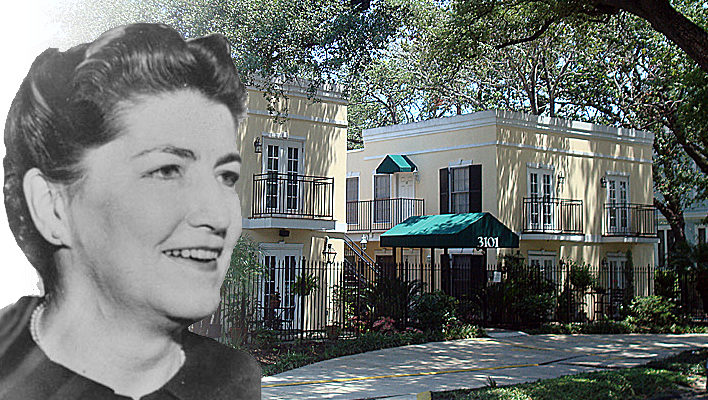

Kennedy had less trouble with other important matters in life. Like his father, he had an early interest in women. Jack had a large number of girlfriends and mistresses. Friends later claimed that the energy at parties tripled when Kennedy arrived. Men wanted to be like him, and women wanted to be with him. He had a high libido, declaring that he couldn’t go three days without a woman. The only woman who could truly be called Mrs. Kennedy was Jacqueline Lee Bouvier (1929). They met in 1951, and soon a relationship developed. Joe must have watched with satisfaction; it was again the powerful senior who had orchestrated the meeting. He had met the attractive photojournalist from the Times-Herald in 1950 and found her suitable. Jackie was in England for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II when she received the marriage proposal via telegram. They married in September 1953, and Joe organized and paid for the massive media event with 1,300 guests.

Three years later, the couple had their first child. Arabella was stillborn, and Kennedy was enjoying himself on a vessel in the Mediterranean at the time. Daughter Caroline followed in 1957, John Fitzgerald Jr. was born in 1960, and in 1963, John and Jackie lost another baby, Patrick Bouvier, who died three days after birth. The whole of America sympathized with the family. John F. Kennedy had been president of the United States for some time by then.

The campaign for the White House

Kennedy had three competitors within his own party for the presidential nomination. His future vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, was one of them, but the main rival was Hubert Humphrey. The entire Kennedy family contributed to their most significant campaign. Additionally, their candidate had an excellent campaign team with the best writers, pollsters, and managers. The budget was almost $275,000 (although estimates vary up to $5 million), compared to Humphrey’s meager $25,000. Kennedy had little to worry about. His party’s ticket was practically secured before the actual election at the convention in Los Angeles.

At the Republican Convention, Richard Nixon was elected as the presidential candidate. The two men were only four years apart, and both began their political careers in the House of Representatives in 1946. However, Nixon had much more relevant experience; he had served as vice president under Eisenhower for eight years. The 1960 election campaign would be remembered as the first fought, in part, on television. In a series of debates, charismatic and confident Kennedy faced off with the sweating, awkward Nixon. The new medium seemed tailor-made for John F. Kennedy. Presentation and image suddenly became crucial in the race for the White House, and Kennedy handled it shrewdly. Nixon later called Kennedy’s team the most ruthless group ever deployed in a political campaign. Kennedy repeatedly cornered his opponent by addressing sensitive issues where, given his position as vice president, Nixon couldn’t reveal everything.

Kennedy aimed to appeal to all segments of the voting public. Women were not an issue for him; Kennedy’s hands often bore scratches from the long nails of women who wanted to touch him. But for other groups, he had to make more effort. He had black Americans in his pocket when he called Martin Luther King’s wife and openly supported her when her husband was briefly jailed for his fight for civil rights—something Nixon had refused. Coretta Scott King said, ‘I have a suitcase full of votes, and I’m taking them to Kennedy.’

In the battle for the world’s most powerful position, both candidates resorted to clandestine means, involving figures from the underworld. Nixon was determined to bring down Castro’s Cuba by any means necessary, thinking it would secure the White House. The Eisenhower administration, with the CIA, planned an invasion of Cuba. But to ensure victory in the elections, they believed Castro had to be killed. With White House approval, the CIA enlisted the help of the Mafia. It sounds almost unbelievable, but as this book will later reveal, this is how things worked in the early 1960s, and they were irrefutably proven many years later. All the facts eventually came to light, including instances when the Mafia assisted Kennedy during the 1960 elections. The seventy-two-year-old father of the presidential candidate made emergency plans for uncertain states and needed the Mafia for that. Especially in Chicago, Illinois, they had considerable influence within the unions. This way, the Kennedy family bought votes on a large scale. The dangerous connections yielded a massive win for Kennedy in Chicago, although the victory in Illinois was marginal. The Republicans smelled something fishy but couldn’t prove anything. In the battle for the most powerful position in the world, everything was fair game – Joe Kennedy didn’t need to be told: ‘Things don’t just happen. You make them happen.’

Kennedy ultimately won because he had more money, a better-organized campaign, and effectively used television as a campaign tool. The 1960 election between Kennedy and Nixon was one of the most exciting of the twentieth century. Kennedy won by a narrow margin of 120,000 votes, the closest victory since 1884. No one could have foreseen that Kennedy’s triumph would drastically change America’s future.

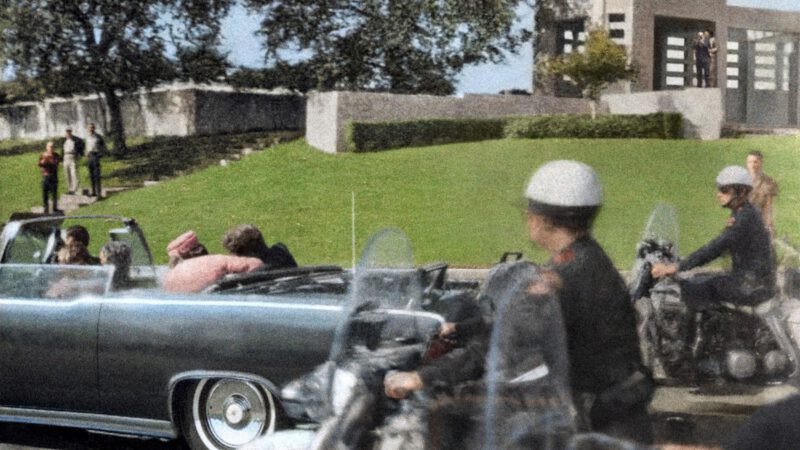

What happened next? He became the President of the United States. Read more on his thousand days in the White House here.

2 thoughts on “Kennedy’s youth: the man before he became the President”