Oswald’s CIA contacts in Europe

In the last years of his life, Oswald came into contact with various individuals with a proven history with the CIA. This article is about Oswald’s CIA contacts in Europe.

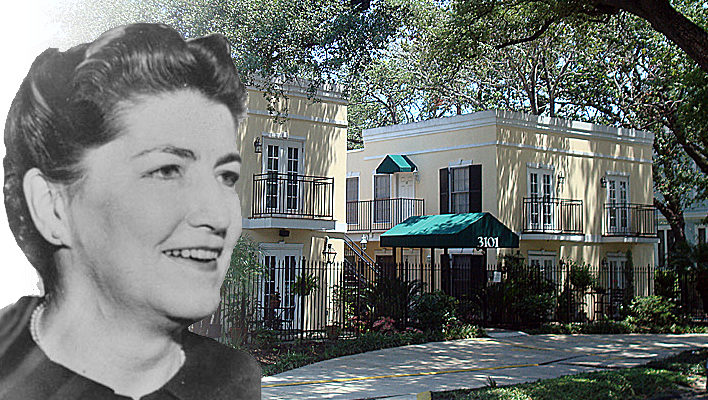

Priscilla Johnson McMillan and John McVickar

One of them is Priscilla Johnson McMillan (pictured above). She passed away in 2021 at the age of 92. We exchanged emails in 2007. She had a very interesting biography, having come in contact with both John F. Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald during her lifetime.

Born in 1928 into a wealthy family on Long Island, McMillan applied for a position at the CIA after graduating in 1952. Initially rejected, she was labeled as ‘interesting for the future.’ In 1953, she worked for John F. Kennedy, a young Senator in Massachusetts. Fluent in Russian, McMillan served as a translator for the U.S. embassy in Moscow from 1955 to 1957. She maintained regular contact with the CIA during this period. After 1957, she visited Moscow several times for unknown reasons, and in November 1959, she was there again as a reporter for the North American News Alliance. She stayed at the same hotel as Lee Harvey Oswald. She learned about his presence on November 16 from her old friend John McVickar, the close associate of Ambassador Richard Snyder – the man who had Oswald at his desk shortly before. McMillan and McVickar knew each other from their time at the U.S. embassy.

John McVickar, like much embassy personnel at the time, was on the CIA payroll, a fact that became clear later when investigators examined his questionable activities during those days. Despite Oswald’s case falling under his superior Snyder’s jurisdiction, McVickar unusually involved himself with the young emigrant. To justify this, McVickar later claimed he feared unnecessarily provoking Oswald’s anger, which would strengthen Oswald’s resolve to renounce his citizenship. McVickar thought to appease Oswald by introducing him to a woman: his girlfriend, Priscilla McMillan. Snyder later stated he disapproved of his young colleague actively meddling in the Oswald case, especially the pressure he exerted on McMillan, displeased him. “Don’t forget you’re an American,” McVickar reportedly said, adding, “There’s a thin line between your duty as a journalist and your moral duty as an American.” McVickar’s manipulations clearly went too far.

On the evening of November 16, McMillan had a lengthy interview with Oswald in her Hotel Metropol room. Oswald was candid. McMillan wrote an article (see photo) based on the conversation, published on November 26, 1959, in the Washington Evening Star. However, she omitted crucial details, such as Oswald’s disloyal promise to pass secrets to the Russians. After the murder, McMillan stated that she felt sympathy for Oswald due to the position he had maneuvered himself into and didn’t want to worsen it by publishing such matters.

On November 17, McVickar and McMillan met again. Richard Snyder later commented, “McVickar’s interference in the case was already curious and wrong, but even more unprofessional was that he discussed the case with the press.” It is more plausible that, while an ambassador and a journalist were in conversation, their connection was mainly through their joint work for the CIA. This is evident from more striking events. On the evening after the meeting, John McVickar wrote a peculiar report on his conversation with McMillan, titled ‘A Memo for the Files.’ He authored a report full of falsehoods and placed events in an incorrect sequence, likely to conceal his involvement. Two days later, on November 19, he added a postscript: “Priscilla approached me with news: she heard that Oswald is leaving his hotel at the end of the week and will receive training in electronics. She has asked to stay in touch, and he apparently already had some reservations about the Soviet Union.” However, McMillan did not have any further contact with Oswald that week. McVickar’s mention of electronics training was the most curious part. At that time, Oswald didn’t even know he would be sent to Minsk, let alone that he would work with electronics in that provincial city. How did McVickar get this information so early? This was a mystery even to Richard Snyder.

They were not the only CIA employees in Moscow; ambassadors like Russell Langelle and George Winters were later revealed to also work for the intelligence agency. However, in the Oswald case, McVickar and McMillan seem to play significant roles in those initial weeks on European soil. McMillan’s involvement did not end after Kennedy’s assassination. In 1964, she contacted Marina Oswald, and a close friendship developed. In 1977, her book “Marina and Lee” was published. McMillan firmly believed that the Warren Commission had it right. She considered Oswald perfectly capable of assassinating the president. She ignored her CIA past in her work. At the time of the publication of my first book, in 2008, the elderly McMillan was associated with Harvard University in Massachusetts as a historian.

Leo Setyaev

Leo Setyaev is another name mentioned by various researchers. He was a radio journalist who sought out American tourists to interview them about their time behind the Iron Curtain. Setyaev had American relatives who, like Oswald, had turned their backs on their country. The journalist and Oswald first met in October 1959, officially for the radio program. Lee Harvey Oswald was not the only traitor who ended up in the Soviet Union. Lists circulated within the CIA at that time with Americans residing in Russia, including Oswald. The CIA closely monitored individuals like Robert E. Webster, Bruce Davis, Libero Ricciardelli, Vladimir Sloboda, and Joseph Dutkanicz, all of whom, like Oswald, had ended up in the Soviet Union after their flight only to return to the United States – except Dutkanicz, who died in the Soviet Union in November 1963. Such emigrants were of great importance to the U.S. government as they could provide valuable information about life in the Soviet Union. There is evidence of contacts between the American defectors and Setyaev. For example, Dutkanicz had a meeting with the radio journalist in Lvov on July 10, 1960. Vladimir Sloboda also had contact with him before his trip to the U.S. Setyaev was also in contact with Oswald. He wrote his own name and contact information in Oswald’s notebook, a fact Setyaev did not deny when questioned in 1991. He did deny ever having relationships with the CIA. Setyaev visited Oswald several times in the first months. They even attended a film night together at the Hotel Metropol. Even after moving to Minsk, there was occasional contact. There was an appointment on July 8, 1961, when Oswald briefly returned to Moscow. And when Oswald was arrested on August 9, 1963 (over two years later!) in New Orleans after a street brawl, Setyaev’s contact information was found in his pocket.

During his time in Minsk, Oswald was officially not allowed to leave the region, but there are several witnesses who claimed to have seen him in Moscow afterward. What exactly he was doing there will never be known, but the visits provided ample opportunities to meet individuals like Setyaev. The most remarkable statement came from American tourists Monica Kramer and Rita Naman. In the summer of 1961, they traveled to England, bought a car, and then drove to Eastern Europe. In Moscow, they met American Marie Hyde at the National Hotel. They decided to travel together. On August 1, with their guide, they visited the Moscow film festival. In the evening, they encountered a man who briefly spoke to them in English with an American accent. Just over a week later, the trio was in Minsk. They parked their car on October Square, near the Stalin statue that would later be taken down that year. The unusual car attracted the attention of the local population, and the women took two photos of the curious Russians. Then they realized that one of the men near the car was remarkably the same person they had spoken to briefly in Moscow nine days earlier. The women would never forget at least one aspect of their days in Minsk: shortly after the meeting, they were questioned by the Russian authorities without knowing what it was about. Upon returning to America, they were also questioned by the CIA – a standard procedure at that time for tourists who had been in the communist world. The CIA reviewed more than 150 photos and made copies of five of them. Suddenly, after JFK’s assassination, two of those copied photos surfaced. The man near the car in Minsk and at the meeting in Moscow turned out to be Lee Harvey Oswald. That Oswald was spotted again in Moscow is already remarkable, but even more striking is that the CIA selected precisely the one where Oswald appeared – while, according to the CIA itself, he was still an unknown man at that time. Is this, too, purely coincidence?

Alexis Davison

In addition to Setyaev, the name Davison is also interesting. Before Oswald could return to the United States with his family, he underwent medical examinations by a doctor at the U.S. embassy, Alexis Davison. This Davison had been working in Moscow since May 1961 and was on the CIA payroll. In May 1963, he had to leave the country along with some other American diplomats, all suspected by the Russians of working for the intelligence service. Some of Davison’s activities have become known and confirmed by Davison, but many are still not public. Strikingly, the address of Davison’s Russian mother, Natalia, who lived in Atlanta at that time, was found in Oswald’s notebook after JFK’s assassination. The plane with the Oswalds, flying from New York to Fort Worth in Texas, made a stopover in Atlanta. What did Oswald need with the address in Atlanta? The clarification of that will probably always remain elusive. In Atlanta, officials also noted that the Oswalds only took five suitcases on board, while according to the papers filled out in New York, they should have had seven suitcases. Oswald explained that he had sent some of his luggage ahead by train, which seems illogical given the longer time it would take for the suitcases to reach Texas. Researchers in the past suggested that Oswald left sensitive material from the Soviet Union here with the only person he knew in Atlanta: Mrs. Natalia Davison.

Michael Jelisavcic

In Oswald’s notebook, the name Jelisavcic also appeared, on a page with notes about Oswald’s weekend in Rotterdam in June 1962 (see photo). The Slavic name was a mystery to researchers for many years, only becoming clear in the early 1990s. Released documents revealed that the CIA knew a lot about this man working at American Express in Moscow, Michael Jelisavcic, in the early stages. Michael Jelisavcic resided in the same hotel as Oswald in October 1959: the expensive Hotel Metropol. After Kennedy’s assassination, the FBI investigated whether Jelisavcic had ties to the Soviet intelligence agency, the KGB. Other sources claim that the man worked for the CIA. Writer and researcher Joan Mellen, who was already working on the case in the 1960s, discovered a document in the National Archives in Maryland at the end of 2006. The memorandum stated that Jelisavcic worked for James Jesus Angleton’s counterintelligence division. Could Jelisavcic be the one who informed the CIA in the early stages that Oswald wanted to return to the U.S.? Own research revealed that the man, born on June 4, 1912, in Montenegro as Mikhailo Jelisavcic, actively dealt with Oswald’s return to America. Sometime in May 1962, an anonymous ambassador in Moscow wrote the following: “Mike Jelisavcic gave me the following cost breakdown for the train journey. […] I believe that the extra convenience of the already arranged housing in Rotterdam justifies this route.” A very interesting memo: the first and only physical evidence of contact between the embassy and Jelisavcic about the fate of the Oswalds. Perhaps he is also the one who reserved the boat tickets at the American Express office on Meent in Rotterdam. More importantly, what did they mean by the already arranged housing? (In English, the writer referred to it as a ‘ready-made shelter arrangement.’) No one has ever been able to explain what that accommodation exactly entailed and who arranged it. Did it refer to the expensive boarding house on Mathenesserlaan? In August 2007, I had an email conversation with Jelisavcic’s son Micha. He didn’t remember anything from the time in Moscow; he was still a child. His father had been dead for some time. Confronted with his father’s role in Lee Harvey Oswald’s life, Micha Jelisavcic initially reacted surprised. Jelisavcic, residing in the village of Dumfries in Virginia just sixty kilometers from the capital, Washington DC, had never heard from anyone that his father had ever dealt with the alleged assassin of John F. Kennedy. He was surprised that no researcher had ever tracked him down, given his father’s history at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Yugoslavia and his time in the South African air force. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Serbia responded helpfully and promptly sent their dossier with documents related to Jelisavcic. According to those papers, the Montenegrin born on June 4, 1912, had indeed been working at the ministry since 1937 and fled to Africa just before the outbreak of World War II. There was even correspondence from Cairo: Jelisavcic was a well-traveled man. The friendly conversation with son Micha quickly ended when it became clear that I was mainly interested in his father’s possible work for the CIA and not in his book on Russian art and architecture in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Returning home

Oswald’s application for all the necessary papers for his return to the United States went surprisingly smoothly. At the height of the Cold War, a potentially dangerous defector could return to his homeland, along with his Russian wife and child. There was never any sanction. These remarkable circumstances, too, raise at least some questions.

2 thoughts on “Oswald’s CIA contacts in Europe”