A conversation with expert Peter R. de Vries

In 2006 I worked several months at the editorial team of Peter R. de Vries, a famous Dutch investigative journalist and crime reporter. For decades he was well known in the Netherlands for his works in unsolved crimes; unfortunately he was assassinated in Amsterdam in 2021. My role in the editorial office was modest; I was there as part of my graduation during the final months of my studies. In May 2006, De Vries presented a 2.5-hour program on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It was a very impressive broadcast. I was able to assist a bit in the background; around that time, I had already been involved in the case for two years. I could occasionally provide substantive advice and observe during the writing process. De Vries, along with some colleagues, made an envy-inducing trip to America to film on location.

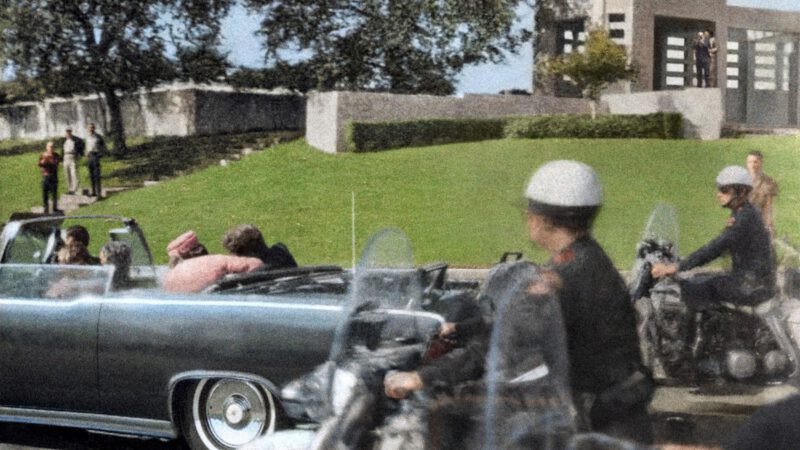

I remember very well how that broadcast began: the crime reporter kicked a ball from a field in the Netherlands and then caught the ball on Dealey Plaza. He mentioned that he heard the news while playing soccer; he had just turned seven a week earlier. I have fond memories of that time, being so close to the action. Crime has always fascinated me greatly.

I have always stayed in touch with Peter R. de Vries. When my first book was released, he talked about it on the well-known TV program RTL Boulevard. For my second book, I had the opportunity to interview him; in the final chapter, I had experts discuss the crime of the century. I spoke with him at his new office, in the shadow of the Ajax football stadium in Amsterdam. Earlier I had worked with him at their old location, in Hilversum.

I will discuss his lengthy Kennedy broadcast in another article later. Below is the full text from my second book: the conversation with Peter R. de Vries in May 2012. I unfortunately did not take a photo during my interview with De Vries. However, in 2017, five years later, I did capture the moment when I encountered him at another event. You can find that photo at the very bottom of this page.

In 2006, I was in the final stages of completing my studies. I was working on my graduation project at the editorial office of Peter R. de Vries precisely during the season when he was working on his extended broadcast about the assassination of Kennedy. De Vries had been interested in the Dallas murder for many years, but after writing a column for Panorama in 2001 and receiving numerous responses, he became truly captivated by the tragedy. At that time, he wrote about his ‘unspoken desire as a crime reporter, whose territory is always bounded by Dutch dikes, to be involved in such a real-world case for once.’ The fascination culminated in the lengthy broadcast five years later, watched by around 800,000 people. The crime journalist started on a soccer field in Amstelveen: ‘Here, in front of my parental home, I learned about the murder. I was only seven years old, but it is still vivid in my memory. History was being made at that moment. The murder case every crime reporter dreams of, but whose true details are literally and figuratively unreachable far away.’ Is there a more well-known authority in the Netherlands on the Kennedy assassination? It seemed logical to start my journey through the authorities on this subject with a conversation at the editorial office in Amsterdam. De Vries gladly invited me for a discussion, with his right-hand man, Kees van der Spek – the director of the 2006 broadcast – also present. De Vries: ‘I always enjoy talking about this case. Even now, as we discuss it, I get enthusiastic. All the adventures we experienced in 2006 in the United States come flooding back, all those question marks. We ate at the pancake house where Jack Ruby, according to our witness, was on the morning of Kennedy’s murder; we were chased from a property by someone who left an impression; we met intriguing people. We had unexpected encounters at the murder site, with, for example, someone who pointed to himself in a faded photo among the spectators on Elm Street on the fatal day. We visited the schoolbook depository and spoke with researcher Robert Groden, who kept looking around nervously to see if the police were coming, fearing reprimand for selling magazines and other ‘conspiracy theory propaganda’ in public spaces. All very special.’ De Vries genuinely hopes to live to see the day when the events of 1963 are finally clarified. ‘Sometimes you see in the newspaper that, due to new techniques, a murder is solved that happened a hundred years earlier.’ Laughing, ‘It would be nice if, as an old man, I read somewhere in a small news item on page 21: “John F. Kennedy, a former president of the United States, was murdered by the CIA in 1963.”‘

The preparations for the 2006 broadcast bring back only pleasant memories for him. De Vries: ‘I don’t think I’ve ever felt so blessed with my job. To be there, at that special Dealey Plaza… You really have to go there as a researcher: it’s better than watching a thousand films of the location. The visit to the museum in the schoolbook depository was an eye-opener. In hindsight, I have gained more appreciation for the Warren Commission. Men who, at that time, didn’t know what we know now and couldn’t do what we can now. It was a different time. You can easily get swept away by theories, but after our research and conversations with experts, things often turn out to be more explainable than you think. That magic bullet, for example, you can show it in a ridiculous, cynical way, as Oliver Stone did in his film JFK. But is the trajectory of that bullet really so absurd? A bullet can make remarkable contortions in a human body… And the wound in Kennedy’s head, which according to some proves that a shot must have come from the grassy knoll. What do we really know about that matter? What is our frame of reference? What is logic? I must confess: there is no case with as much material for a conspiracy as in this case. But can you imagine that in fifty years, no one has ever leaked anything? All those people at the CIA, at the Warren Commission, you name it: no one has ever leaked with demonstrably good evidence. Not even their family members. That is disturbing, peculiar, and unbelievable. A one in 7 billion chance that such a secret remains hidden, and yet it happened here. Astonishing.’ The multitude of new theories and testimonies, according to the crime journalist, also makes the case increasingly complex. ‘When Fortuyn was shot at the Mediapark, where we still had our editorial office at that time, I heard a theory about parking attendants intentionally waiting to let ambulances through. Well, I knew all those men, I am sure they did nothing that day that couldn’t bear the light of day. But elsewhere in the country, such a story is picked up and believed. It just shows how difficult it is to assess how seriously a theory should be taken. So much in the Kennedy case nowadays must be taken with a grain of salt.’

In his own broadcast, De Vries mainly addressed the story of James Files, the criminal who claimed to be the shooter on camera. Effortlessly, De Vries recalls facts from memory, occasionally assisted by the two JFK folders in his impressive filing cabinet: ‘I still stand behind the facts we presented in that broadcast six years ago. The story of FBI investigator Zack Shelton has never been debunked by anyone, and even after extensive research, we found nothing. At that moment, Files could have been at that location, was connected to the mafia, and never contradicted himself. But what stood out the most: he spoke very vividly during his confessions, from his memory, with a lot of body language. Liars don’t do that. You know what I sometimes think about? Kennedy was riding in that parade through Dallas. Somewhere, a man with a video camera stands, and as luck would have it, he films the murder. What if the murder had happened in our time? The FBI would beg the public to stop sending material after two days: the bullet impact would have been captured from a hundred different angles. You saw that with, for example, the attack in Apeldoorn on Queen’s Day 2009. Many images were quickly available on the internet. Whoever was responsible in 1963, they were helped by the times back then. The lack of good evidence has ensured that it is still a mystery. And, of course, the fact that Oswald was quickly eliminated. Jack Ruby fired only one shot, and it was instantly fatal. That’s the typical bad luck that can occur. For all we know, you could survive such an attack…’

John F. Kennedy became a myth due to the bullets on Dealey Plaza. ‘He never had the time to make big mistakes,’ Peter R. de Vries said, ‘And that probably contributed to his good image. Besides, of course, his appearance and charisma. After all those gray gentlemen, there was finally a young guy in the White House, with a nice, appealing family. Kennedy brought hope with him, and suddenly, that hope was gone. By now, that mythical image has been adjusted somewhat, thanks to statements from women who claim to have had affairs with the president. But then I say: which president of the United States has adhered to marital fidelity?’

One thought on “A conversation with expert Peter R. de Vries”