Willem Oltmans investigating George De Mohrenschildt

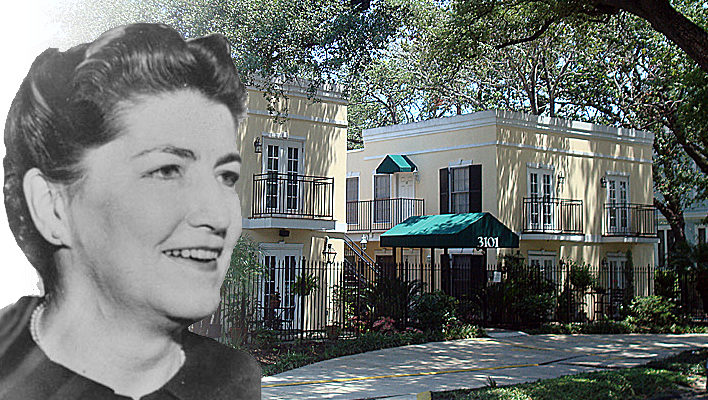

On September 30, 2023, Lammert de Bruin and Babs Assink from the Dutch broadcast organization AVROTROS visited me for an interview. They were working on a new podcast series about the Kennedy assassination, leading up to the sixtieth anniversary of the event eight weeks later. For the occasion, I had laid out a portion of my archive on the table downstairs; the collection of books and magazines, my own research, and much more. An enjoyable afternoon ensued (photo on the right). The six episodes were released on November 6 on all podcast platforms, and the perspective of JFK: The Missing Link is unique: they follow the trail of the Dutch journalist Willem Oltmans, who passed away in 2004 (above this article he is pictured next to Marguerite Oswald, the mother of the alleged assassin). This colorful journalist had become friends with an American oil baron of Russian descent who, at the end of his life, confessed to having given his friend Lee Harvey Oswald instructions for the JFK assassination. Who was this George De Mohrenschildt, and was he telling the truth? An intriguing fact: it is Willem Oltmans who appears in Oliver Stone’s famous film JFK, playing none other than his old friend George De Mohrenschildt.

In America, the podcast makers spoke with Paul Gregory, Ruth Paine, Edward Jay Epstein, a former CIA official and the director of the Sixth Floor Museum. They visited Marina Oswald’s property like I did, with just as much success as I had ten years earlier. A very fascinating series; below, I outline it, with some personal additions here and there.

In the footsteps of Willem Oltmans

Episode 1

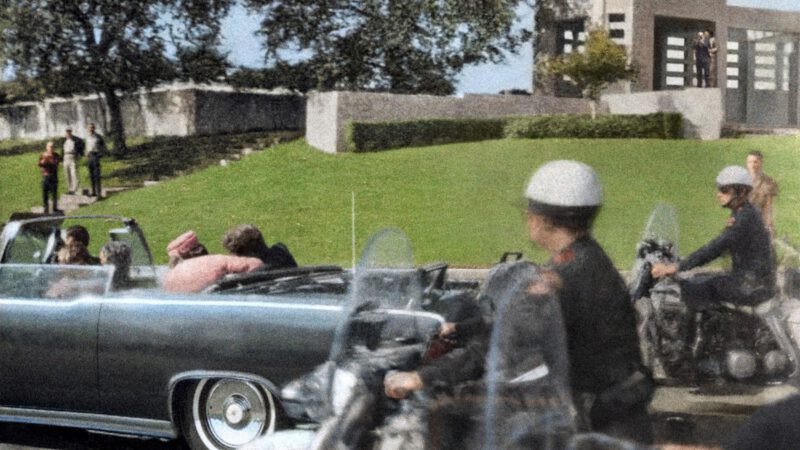

The makers take us back to that Friday in Dallas, November 22, 1963. An introduction for listeners less familiar with all the backgrounds. Assink and De Bruin are on-site at Dealey Plaza. Two days after the assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald is also shot, and ten months later, the Warren Commission report is released. However, due to gaps and unanswered questions, the true circumstances of the murder always remain under discussion. Notably, a new parliamentary investigation is conducted in the 1970s: the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA). Their main conclusion: Oswald did not act alone. One of the sources for the investigators: Willem Oltmans. On April 1, 1977, he declared to the HSCA that George De Mohrenschildt had told him he gave instructions to Oswald at that time.

In Amsterdam, the journalists meet Arendo Joustra, secretary of the Willem Oltmans Foundation. He talks about the colorful Oltmans: eminent, outspoken, connections in the highest circles, controversial, posh, flamboyant, a thorn in the side of the government. “A querulant pur sang,” headlined the Dutch magazine HP/De Tijd in 2019. It was never boring with him. He traveled the world for news for years and had a knack for repeatedly becoming the subject of that news by not shying away from controversies and affairs. He associated with Soekarno and Desi Bouterse and was obstructed for years by Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Luns – which, at the end of his life, earned Oltmans eight million guilders in compensation, paid by the Dutch State. Oltmans wrote diaries throughout his life, and thanks to the foundation, they are being published one by one at a rapid pace. “He was a special journalist, and he had the world as his stage,” says Joustra. “Throughout his entire career, you see him popping up on different continents.” He constantly associated with controversial figures, including Soekarno and Bouterse, but during the War on Terror, he also spoke with the deputy prime minister of Iraq, Saddam Hussein’s right-hand man. “He wanted to hear what they had to say. In a fairly open way. It was not appreciated, but actually, it makes sense to let them speak too.”

But what did Willem Oltmans know about the Kennedy assassination, and how did he become involved?

Episode 2

Episode 2 begins with Willem Oltmans himself. Miraculously, his voice is reconstructed thanks to the new possibilities of AI. Oltmans reads from his diary. In March 1964, he met Marguerite Oswald before a short domestic evening flight from American Airlines to Dallas, Texas. They find themselves seated next to each other on the plane and extensively discuss the Kennedy assassination. Oltmans takes diligent notes. Mother Oswald says: “It is possible that Lee killed the president, but no one has ever proven it. As a mother, I will fight for his rights, even though he is now dead. His guilt should be established according to our applicable laws. Until this happens, I will never be able to believe that he really did it.” The next day, the duo stands at Lee Harvey Oswald’s gravesite, and since then, Oltmans stays in contact with Marguerite. At that moment, Oltmans’ in-depth investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy begins.

Next, it’s time for the conversation with me. I get to talk about my fascination with the murder. I mention that the enormous number of unanswered questions intrigues me; even sixty years later, not everything is clear. I discuss the inadequate investigation by the authorities at the time and express the suspicion that the whole truth will never come to light. The Rotterdam episode is covered: the subject of my first book. Lee Harvey Oswald was in our country on his way to his homeland when, in Minsk, he decided that his Russian adventure was over. The weekend in Rotterdam still holds many mysteries. And why did Oswald consciously create multiple identities from that moment, a kind of smokescreen around his own person?

After the assassination, the CIA claimed they didn’t know Oswald, and the Warren Commission accepted it as true. By now, we know better, and much more information has become available. In 1968, Willem Oltmans interviewed New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, who, with his independent investigation, caused the first cracks in that official narrative. Garrison pointed an accusing finger at the CIA. We’ve all seen this in Oliver Stone’s successful 1991 film, featuring that cameo by Willem Oltmans.

In 1967, Oltmans speaks with the paranormal Dutchman Gerard Croiset, who enjoys some fame in the U.S. as the ‘Amazing Dutchman.’ Personally, I am not a fan of paranormal gifts getting involved in such serious matters, but Oltmans dropped his initial skepticism. In a later interview: “I have seen so much of him that I am now convinced that paranormal gifts exist.” Croiset describes to Oltmans a geologist, a man in his fifties who would have been the architect of the murder plot. That can only be one man, and this is how Oltmans comes into contact with George De Mohrenschildt: the extraordinary best friend of Oswald during his time in Dallas.

Willem Oltmans discusses De Mohrenschildt with a spokesperson for Robert F. Kennedy, after which FBI agents visit the Dutch journalist for an extensive discussion on the same day. The next day, on April 4, 1967, Oltmans has a peculiar car accident in Manhattan, the first in his life. He always thought something was amiss. Was he becoming paranoid? Or was it indeed a serious warning?

On October 15 of that year, Oltmans finally interviews George De Mohrenschildt at his home in Dallas. The interview for Dutch television lasts 45 minutes. Unique material, but the tape goes missing in The Netherlands and is unfortunately never found again. Even a lawsuit by Oltmans in 1975 does not retrieve the tapes. It’s a shame because De Mohrenschildt came up with an interesting story, an explanation that contradicts what he told the Warren Commission earlier. There, he made Oswald suspicious and called him a ruthless murderer. In 1975: “Lee Harvey Oswald could never have harmed JFK because he adored Kennedy as much as we did. Instead of the Warren Commission hiring a battalion of detectives, these gentlemen collected data that had absolutely nothing to do with the president’s murder. The committee only made an effort to try to make it plausible that Oswald had done it.” George De Mohrenschildt shares that he knew widow Jacqueline Kennedy in the late thirties when she was still a child. He associated with members of her family, the Bouvier family. “But that’s purely coincidental, it has nothing to do with the case.”

A friendship develops between Oltmans and George De Mohrenschildt, both of whom have Russian noble ancestors. It creates a bond. The Dutchman stays with him several times, a correspondence ensues. Oltmans hopes that his new friend will eventually come forward with a full confession. And then, of course, it would be with him. He is patient. For now, De Mohrenschildt talks a lot but remains quite vague. His statement about a rifle that Oswald owned remains significant. He is pictured with it: the famous Backyard Photo. Oswald allegedly shot at an ultra-right-wing general in Dallas six months before the Kennedy murder. “The Oswalds were nonchalant about it. He needed the rifle for clay pigeon shooting, Marina Oswald said.” However, in the spring of 1963, De Mohrenschildt can put two and two together. For him, it was clear who shot at General Edwin Walker. Marina later admitted it during the Warren Commission hearing.

Ten years after the first interview, Oltmans is back in Dallas. He calls De Mohrenschildt, and another meeting follows. The geologist is not doing well; he is divorced, paranoid, afraid. To Oltmans, he suddenly declares in February 1977: “I was responsible for the Kennedy assassination, and they are going to kill me. I influenced Oswald, and now it’s fatal for me.” He claimed to have done it on orders from the intelligence service.

A few weeks later, Oltmans takes his friend to the Netherlands. With Dutch media director Carel Enkelaar of the NOS, they visit psychic Gerard Croiset and the Strengholt publishing house on an estate near Bussum. De Mohrenschildt is willing to tell his whole story after the weekend. To pass the time, Oltmans takes his friend to Belgium on Saturday. George De Mohrenschildt once studied in Liège: time for some sightseeing and lunch in Brussels. Vladimir Kouznetsov will also join them at that meal, an old Russian friend of Oltmans now working in Brussels. De Mohrenschildt and Mr. Kouznetsov immediately start speaking Russian together. Before the lunch begins, De Mohrenschildt leaves the duo alone. He does not return. Later, an explanation emerges with De Mohrenschildt’s reasons: he felt pressured by Oltmans and was disappointed in his old friend.

Oltmans reported him missing to the Russian embassy in the Netherlands. A few weeks later, De Mohrenschildt is found dead at a friend’s house in Florida.

Episode 2 ends in Helmond, at my home. When asked, I tell the podcast makers that I am familiar with Oltmans’ investigation, and I have always found his adventure with De Mohrenschildt envy-inducing. I mention that there is no stranger friendship imaginable than that between De Mohrenschildt and Oswald; they are so different that it makes sense that their bond raises questions. The distinguished geologist and the young laborer: a unique alliance. I mention in the broadcast that it later became clear that De Mohrenschildt regularly had coffee with James Walton Moore, the local CIA chief in Dallas. In my view, De Mohrenschildt became a kind of mentor to Oswald, a guide, an influencer.

What happened to De Mohrenschildt after his disappearance from Brussels, in the weeks before his death?

Episode 3

District Attorney Jim Garrison from New Orleans speaks again. In a statement from 1967, he unequivocally states that the CIA was behind Kennedy’s murder and calls the Warren Commission report a fairy tale. How close were he and Oltmans to the truth?

By now, about 98% of the millions of documents from the vault in Washington DC have been released; in recent years, the vault was opened again under Trump and Biden. Journalists Babs Assink and Lammert de Bruin start digging, searching for documents about George De Mohrenschildt. It’s an extensive search for clues about the role of the Russian oil baron from Texas. The documents indicate that he maintained contact with intelligence agents shortly after his arrival in America in 1938. Various sources label him as an informant for the CIA. That he eventually collaborated with the intelligence service can now be established.

The journalists manage to get Rolf Mowatt-Larssen for this episode. He was the Head of Operations Europe at the CIA. Unique: most former CIA officials remain tight-lipped for a lifetime. What does Mowatt-Larssen, who worked at the CIA for 23 years, think about the possible role of De Mohrenschildt and the CIA in Kennedy’s murder? “De Mohrenschildt’s role was crucial in any case,” he says. “He was a key figure, no matter which theory you subscribe to. His bond with Oswald was strong in the year before the murder. We would have known more now if he had told his full story on time. Now, his statements are incomplete. Unfortunately, he committed suicide shortly before his testimony to the new government commission, the HSCA. What more could he have offered us there? It is certain that he seemed much more willing to testify in detail now than thirteen years earlier at the Warren Commission.” On the unique friendship: “In conservative Texas, the leftist Oswald had few friends, and then he met De Mohrenschildt. I always found it hard to believe that George De Mohrenschildt had only personal motives for associating with Oswald. That it was an ordinary friendship without any involvement from the U.S. government.”

The podcast makers travel to New York City and walk to the United Nations building, where Willem Oltmans used to hang out almost daily. In Washington DC, Assink and De Bruin then visit investigative journalist Philip Shenon of the New York Times, who thoroughly researched the work of the Warren Commission. He wrote an excellent book about the Kennedy assassination and the commission’s report. “That report is ultimately very flawed. I have spoken to people involved in the investigation into the murder. Young lawyers, the best people in their field. Although there has been a lot of criticism later on, they were, in their perception, very sincere and diligently searching for the truth at that time. History did not do them any favors, and that was one of the reasons why they wanted to tell their story one more time. They had to deal with organizations that did not show their cards. The CIA, the FBI, but also others were incomplete in their cooperation. Those hardworking investigators could not help it that they were systematically obstructed. The mentioned organizations did their best to portray Oswald as a lonely, dangerous, unpredictable man. Someone they could never have stopped; this murder could not have been prevented. They kept secret that they had Oswald under surveillance in the weeks before the murder. That only became known much later.”

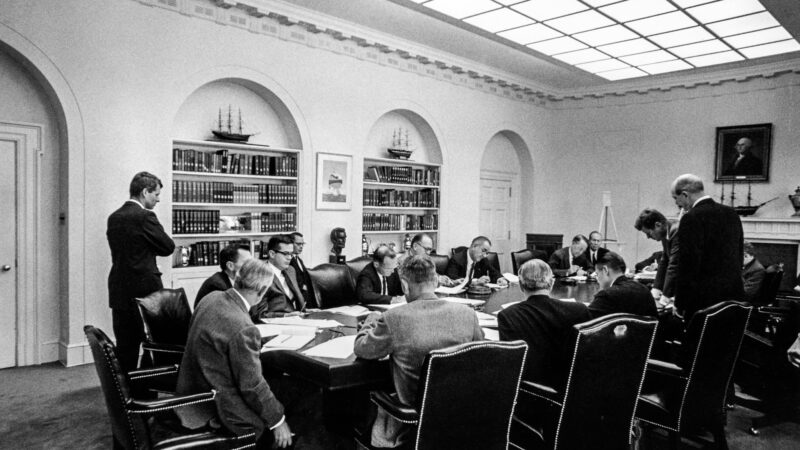

Next, the podcast discusses how the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, came to form the investigative commission. In a recorded phone conversation, J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI, tells the president: “I think it would be very bad if there were an excess of investigations.” The president agrees. And he only wants the commission to evaluate the FBI’s report made within a week. Johnson suggests Allen Dulles as a member of the commission. Dulles is the former director of the CIA, fired by Kennedy in 1962 after the failed invasion at the Bay of Pigs. An remarkable choice, given that dismissal, but also because Kennedy had intended to dismantle the CIA after that invasion, to scatter it into a thousand pieces. Philip Shenon of the New York Times: “Dulles being involved in that commission indicates a conflict of interest. A big mistake. He was involved in a lot of sinister activities at the CIA. That could just continue in that new role at the Warren Commission. Important documents disappeared about, for example, a mysterious stay of Lee Harvey Oswald in Mexico City, two months before Kennedy’s murder. How is that possible? They resurfaced years later, and I showed them to the still-living investigators who were active for the Warren Commission. They were surprised. They had never seen the documents before.” It raises the question of what the CIA knew and concealed in those years. About the role of De Mohrenschildt, for example. Philip Shenon: “He is an important figure, especially considering that friendship with Oswald. He is a person who has caused confusion. When you read about his life, you easily think: this could have been a spy for the CIA. He saw a lot, knew a lot. Unfortunately, he never gave a complete, coherent statement.”

It’s high time for the Dutch journalists to travel to Dallas.

Episode 4

The episode begins again with the reconstructed voice of Willem Oltmans, reading from his diary. In March 1967, Oltmans flew from California to Dallas, where he visited Parkland Hospital immediately due to an infection in his armpit – indeed, the hospital where Kennedy died. After routine treatment, Oltmans spoke with Dr. Ralph Greenlee. According to this doctor, there was no one in the hospital who doubted that JFK was killed by at least two bullets from different directions. In typical Oltmans fashion, he ended up having wine with this doctor in the evening, and they spent hours discussing the murder case. Greenlee: “The murder must have been a conspiracy. The entire staff of this hospital knows how things really happened. It’s disgusting.” Oltmans: “For me, the meeting with surgeon Dr. Ralph Greenlee was an intriguing experience on top of it all. He brought me back to the Dallas Hilton hotel in the early morning hours.”

Babs Assink and Lammert de Bruin arrive in Dallas. At Dealey Plaza, they examine the crime scene and discuss the complexity of the case, with all those different theories, statements, and opinions. In the Sixth Floor Museum at the Texas School Book Depository, they then talk to curator Stephen Fagin. The museum is still heavily visited. I visited it in September 2013, and earlier, I had email contact with the famous predecessor of Fagin, the late Gary Mack – the walking Kennedy encyclopedia. Stephen Fagin: “Memphis was not blamed for the murder of Martin Luther King, Los Angeles was not accused in the murder of Robert F. Kennedy. But Dallas was looked at very differently from 1963 onwards. There was a lot of criticism; if a political murder could happen anywhere, it was indeed in that toxic environment, in that violent Dallas. People from the entire country treated locals differently. I know stories of taxi drivers refusing people from Dallas. It changed only years later, thanks in part to the sporting success of the Dallas Cowboys and the TV series with JR Ewing. This museum opened in 1989. We have now accepted that all of this happened to us.”

Fagin has a beautiful perspective on all the theories that researchers have. “We let our visitors judge for themselves what happened at that time. Anyone who goes to the spot where Oswald stood and looks outside sees their own truth. Those who believe in the Warren Commission scenario see a Dealey Plaza where it was very possible for a sharpshooter with a Navy background to cause an international tragedy within eight seconds. Someone who believes in a conspiracy sees a square with several ideal shooter positions, on top of the grassy knoll and from various buildings. Everything fits perfectly then. You see what is logical for your worldview, what you believe in. According to a poll in 2013, more than 60% envision a square that is ideal for a murder plot. We live in a society where there is a lot of doubt about official narratives. We’ve noticed that for sixty years.” Fagin explains in the podcast that every president makes powerful enemies, and he outlines the motives that various organizations had in the early sixties to kill Kennedy. The curator of the Sixth Floor Museum can talk about it for a full day.

In 1977, Willem Oltmans had his fifteen minutes of fame when he was interviewed by the American TV channel CBS after his interrogation by the new government commission. The Dutchman spoke about the confession of George De Mohrenschildt, who declared to him shortly before that he felt responsible for Oswald’s act. “Oswald acted with my knowledge,” De Mohrenschildt said. Fagin: “That friendship raises questions. That geologist is surrounded by mysteries, and shortly before his death, he finally declared about his connections with the CIA. You immediately wonder to what extent Oswald was being monitored during that period. It’s really a theme within the murder that, when you delve into it, keeps raising new questions.”

They visit the exhibition, and afterward, Assink and De Bruin discuss it on the grassy knoll, where, according to various witnesses, shots were also fired. They meet researcher Mark Oakes at his booth, where I encountered him ten years earlier. That’s not a coincidence because he stands there three days a week, almost thirty years now. He shows books and folders full of documents, there are photos and newspaper articles on a board. DVDs are on his table, and a documentary is playing on a laptop. “I’ve been working on the case for forty years,” he says. “I show people images they’ve never seen anywhere else. I’ve spoken to many eyewitnesses and researched a lot. Of course, I know George De Mohrenschildt too. They wanted to question him, and just before that, he shot himself. Remarkable, the number of deaths in the aftermath of this case.”

The episode concludes in Rockwall, a suburb of Dallas. I was there in 2013, and now, my two compatriots stand on the driveway of Marina Oswald ten years later. The adrenaline flows through their bodies, and I recognize that sensation. They know she wants to be left alone, but trying won’t hurt. I was sent away back then, and the same happens to Assink and De Bruin now. They spent a bit more time hanging around the messy yard than I did: they slammed the doors of their rented Tesla shut and left the key card inside. It took a while for the rental company to rescue them; remote unlocking costs twelve dollars. Unfortunately, they didn’t spend the time waiting at Marina’s kitchen table. “I can’t stand it that she’s sitting here fifty meters from us, and we can’t ask her a question,” laments Lammert de Bruin. “It’s so frustrating that I have so many questions for her, and we have to return home empty-handed. We have her within reach, and she’s still alive. Too bad. But okay. Fortunately, the car is open again. Here we go again…”

They will try elsewhere: there are still two friends of the Oswalds alive.

Episode 5

The episode begins once again with the simulated voice of Willem Oltmans. He discusses the De Mohrenschildt couple in his diary. George, who had worked for the French intelligence during the war, was in Haiti with his wife Jeanne during Kennedy’s assassination. He grew up in Minsk, the city where Oswald spent most of his time in the Soviet Union. This shared connection could be a significant reason why he liked to associate with Oswald: he wanted to talk about the city where he lived over forty years earlier. Additionally, he might have wanted to help the financially struggling Oswald in the U.S. Were these the real reasons, or was there more behind that friendship?

The podcast makers visit Irving, a suburb of Dallas, to go to Ruth Paine’s house. She was an American fluent in the Russian language, and shortly after their first meeting, she became friends with Marina Oswald. After marital problems between Lee and Marina, the heavily pregnant Marina moved in with the Paine family – in October 1963, her second daughter, Rachel, was born. The house in Irving opened as a museum to the public in November 2013. When I visited two months earlier, it was still almost empty. The night before Kennedy’s assassination, Lee Harvey Oswald stayed in this house on West 5th Street. His weapon was in the garage, and before leaving for work at Dealey Plaza, he left his wedding ring on the bedside table. It’s a unique place, and anyone walking in nowadays is transported back to 1963. Every effort has been made to reconstruct the furnishings of that time: as if Ruth and Marina could walk in at any moment to watch Kennedy’s motorcade through Dallas, just as they did on November 22, 1963. Their lives changed shortly after.

According to official Kevin Kendro, Ruth Paine was immensely helpful in the reconstruction. He says in the podcast, “She sent hundreds of family photos from that period. Then we looked for similar furniture at antique shops and flea markets. In the garage, we placed boxes; the Oswald couple could store their household items here back then.” Among these boxes, Ruth Paine heard after the murder, was hidden the Italian Mannlicher-Carcano rifle later found at the crime scene. Agents were at the front door in no time, and Marina knew about the weapon. It was a surprise to her that the rifle had been taken by her husband that morning.

Ruth Paine has had a lot to endure since 1963. She is still occasionally harassed by conspiracy enthusiasts, and articles are still published full of insinuations about her ties to the CIA, among other things. She is now 91 years old and living in Santa Rosa, California. Darn, I passed through that city on my way to a winery in Napa Valley in 2019. I would have liked to visit her, as Babs Assink and Lammert de Bruin did for this podcast. She kept quiet for a long time, but in recent years, she has opened her doors to journalists more frequently.

The Russian community in Dallas and Fort Worth was close-knit sixty years ago. It consisted of immigrants and people wanting to learn the language. At a gathering of that club, Ruth Paine met not only the Oswalds but also George De Mohrenschildt. She recalls from that time, “I mainly spoke with Marina because everyone else spoke English with each other. Marina spoke only Russian, so I took care of her. She was there with little June, and as mothers, we talked about everything mothers talk about. And about life in the U.S. Soon after, I visited them in their apartment. I had a lot of sympathy for her. Less so for her husband Lee. I noticed that he enjoyed it when others wanted to listen to his story. He wasn’t very communicative with me.”

In Tennessee, Assink and De Bruin visit 82-year-old Paul Gregory, who also knew Oswald from Russian community meetings. His parents were Russian immigrants, and his father Pete taught Russian. Paul and Lee learned the language together, practiced dialogues. Paul Gregory also did not talk about the murder case for a long time, but in 2022, he published a book about his memories of that time. “I saw him as an acquaintance, but he might have seen me as a good friend. I thought he had some talents. But he was also manipulative. He influenced people, got them on his side, including his own wife. Apart from me, he had few friends. And then, of course, there was George De Mohrenschildt.”

George De Mohrenschildt once spoke with Willen Oltmans about that friendship. “People are surprised about the connection I had with him. I was always professionally interested in people of different backgrounds. Others ignored him; some were shocked by his outspoken character, found him a miserable guy. However, I was intrigued, and he appreciated that.”

The Oswalds were the talk of the town due to their recent return from the Soviet Union, says Paul Gregory. “People were excited, wanted to meet Marina. At that time, it was very unusual for people to come from there. In the summer of 1962, we met regularly. Initially, I sensed some hesitation in others. Was it safe to be around them? Someone even approached a lawyer. But it was said that they were being watched. No one needed to worry. It quickly became enjoyable, with books and maps. Marina told us where she had lived. She looked beautiful in her red dress. The contact with Lee was more challenging. He could react unfriendly or insist on talking about Marxism, for example.”

The community of affluent Texans embraced Lee and Marina Oswald, and one of them was George De Mohrenschildt. He once told Willem Oltmans how he introduced Ruth Paine to Marina Oswald during a gathering. Paine remembers little of that moment sixty years later. “I barely spoke to him. He was a handsome guy, outgoing. But I didn’t meet him very often. His wife was there too. They seemed like nice people,” says Paine. Paul Gregory adds, “I probably met him at those gatherings too. He was a unique guy, an imposing figure. A man surrounded by mysteries; it’s hard to describe him accurately. But I don’t recall specific details of our meetings.”

On November 22, 1963, Marina enjoyed a rare opportunity to sleep in, having two small children. Later, she joined her hostess, and together with Ruth Paine, she watched President Kennedy’s visit to Dallas on TV. Around one o’clock that afternoon, the news of the president’s death arrived, and two hours later, the first agents showed up. Paine says, “It was shocking. The night before, he was still tinkering in my garage. I was there to pick up some toys.” The next day, investigators were in the same garage in that small house in Irving. She is still emotional when talking about that day, even sixty years later. “Unfortunately, I never spoke to Marina again after those dreadful days. It was a terrible time for both of us. It could never be truly pleasant again.”

Paul Gregory was studying in Oklahoma when he heard about Kennedy’s assassination. A normal school day quickly turned into something else. “Shortly after, I saw Lee Harvey Oswald on television, and I recognized him immediately. At first, I didn’t take it seriously; of course, they arrested him. I knew about his communist ideas; such a man is suspicious. Soon after, it became clear that there was a serious reason why he was arrested. My father and I were also on a list because we associated with Oswald the previous year. We were interrogated, even on the day of the murder. A day and a half later, I saw on TV how Oswald was murdered. It surprised me that he died from a shot in his belly. I thought the doctors could still save him. It was a shocking time, traumatic days that gave me nightmares for a long time. It marked my life.”

Both Ruth Paine and Paul Gregory assert that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. He wanted to make history, be seen, and make a name for himself: they are convinced of this. But what about George De Mohrenschildt’s confession? And what exactly happened in the last days of this mysterious friend of Lee Harvey Oswald?

Episode 6

Oltmans is once again speaking, reading from his diary. He reads about the newspaper report of George De Mohrenschildt’s death. Suicide. On March 29, 1977, he shot himself in the head with a double-barreled shotgun in the house of a friend in Palm Beach, Florida. He took everything he knew to his grave. He was 65 years old. Another witness who dies under unclear circumstances, the headlines read. On that morning, he had a lengthy conversation with journalist Edward Jay Epstein, after which he found out that someone from the House Select Committee on Assassinations wanted to talk to him about Kennedy’s murder. It apparently became too much for him. He had talked about suicide before, and things were not going well for him. In 1976, he even underwent electroshock therapy in a psychiatric institution. He suffered from paranoia, and he wrote about it at the end of 1976 to an old acquaintance, George H.W. Bush – the future president who was then the director of the CIA. All signs, and yet Willem Oltmans doubts in his diary. Was it really suicide?

The Dutch journalists track down the now 88-year-old Edward Jay Epstein. After months of back-and-forth emails, they have a conversation in New York City. He became interested in George De Mohrenschildt soon after Kennedy’s murder. “He was an important witness. Important members of the Warren Commission also found his background very suspicious. He was a significant friend of Oswald, which was already unusual in itself, being a member of the highest social class. He looked like a dignified movie star.” In 1977, Epstein writes a biography of Lee Harvey Oswald. He wants to interview De Mohrenschildt for it, and they agree on four thousand dollars for an interview that will last four days.

They meet at the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach on Tuesday morning, March 29, 1977. The first few hours are about De Mohrenschildt’s past and the attack Oswald made on the right-wing general Walker in the spring of 1963. They part ways around lunchtime, planning to continue around 2:00 PM. However, De Mohrenschildt does not return. They wait for an hour and then call Nancy Tilton’s house, the friend he was staying with. She informs them of the news. George De Mohrenschildt is dead. He shot himself with a hunting rifle, with the barrel in his mouth, sitting in a chair on the first floor of the house on 1780 South Ocean Boulevard. A less than elegant end for such a distinguished man.

Nancy Tilton had coincidentally turned on a cassette recorder to record her favorite soap opera, The Doctors, while she went to a beauty salon. This way, she could keep up with the storyline. De Mohrenschildt’s footsteps and then the gunshot at 2:21 PM are clearly audible on the tape. The evidence that there was no murder involved: no other footsteps were heard. However, there are also speculations about this case. Perhaps the intruder wore sneakers, undetectable by the recorder. Or maybe the tape was tampered with. According to Edward Jay Epstein, anything is possible. Several experts point out that it was not possible for De Mohrenschildt to pull the trigger with the long rifle in the mouth.

It soon turns out that someone visited the house where De Mohrenschildt was staying, between 10:00 and 11:00 AM that morning. It was Gaeton Fonzi, a representative of the committee re-investigating Kennedy’s murder: the HSCA. De Mohrenschildt learned about it upon returning home and reacted shocked and angry. Then he went upstairs.

The session with Edward Jay Epstein was supposed to last three and a half days longer, but in the short period they spoke, the journalist got the impression that De Mohrenschildt knew more than he had ever stated to the Warren Commission. “According to him, Oswald was not a strange idiot,” Epstein says. “He did have something going for him. And he had strong ideas about America. I think De Mohrenschildt had a lot more to tell. During our session, he was very candid. We are now in different decades. The chance that the truth about Kennedy’s murder will ever come out is getting smaller.”

Epstein suspects that the CIA was involved in both Kennedy’s murder and the alleged suicide of De George De Mohrenschildt. Willem Oltmans was even convinced of this. Even former CIA agent Rolf Mowatt-Larssen from episode 3 does not rule out involvement of his own intelligence agency in Kennedy’s murder. “It could be that a select group of people within the CIA was involved. Experienced specialists with the right connections who used Oswald for their secret operation. But it’s hard to prove. And you can wonder if those involved can keep a conspiracy secret for sixty years. But in our worst days, the US intelligence agency has done worse things in the world. Secret regime changes, successful or not assassination attempts. There was hardly any oversight; much could be concealed. There is still much we don’t know. I would like all documents to be released now. The search for the truth never ends. Kennedy’s murder resulted in the largest series of unanswered questions in American history.”

Stephen Fagin of the Sixth Floor Museum does not take a stance on all conspiracy theories. “We only help the public navigate through an interpretive minefield of American history.” Philip Shenon of the New York Times is clear: according to him, Oswald was the sole shooter. “If you had to recruit someone for that murder plot, Oswald would be the last person you would choose.” Whether others like George De Mohrenschildt knew about it, he leaves it open.

The podcast makers do not have the illusion that they will solve the murder with this series. Willem Oltmans might have come close. He was convinced that he was close when he was chasing the mysterious George De Mohrenschildt. Oltmans in an interview in 1997 with Dutch interviewer Theo van Gogh: “He felt responsible for Kennedy’s death and Oswald’s death. He told me that himself. They used Oswald. It had to appear as if he was the only shooter. De Mohrenschildt knew about it and later regretted it. He also knew well that Oswald would be murdered. He gradually regretted that a lot.” According to Oltmans, Kennedy’s murder was necessary because he did not want to fight enough against world communism. He was weak in his fight against Castro and wanted to reduce activities in Vietnam. The CIA had other interests, as did the Department of Defense, the military forces, Cuban exiles who wanted to eliminate Castro, mobsters who wanted to make money again in Havana and felt threatened by the ambitious Kennedys, and so on. John F. Kennedy had powerful enemies. His successor Lyndon B. Johnson made decisions that received more approval from the mentioned parties.

In 2038, the very last pieces from the National Archives will be released. Maybe more will be clear then. The podcast series concludes with none other than Willem Oltmans himself. For the last time, we hear the AI-reconstructed voice. “Thank you for listening.”

Willem Oltmans died on September 30, 2004, at the age of 79 in his home in Amsterdam. He suffered from cancer and chose euthanasia due to the hopeless suffering. I did an internship at the Dutch TV program Barend en Van Dorp back then, and I remember well that his end of life was announced during the editorial meeting that morning. If I remember correctly, a floral arrangement was sent to Amsterdam. Willem Oltmans was a colorful man who lived nine lives in those 79 years granted to him.

There is much more to tell about George De Mohrenschildt. I will write more on him later. Babs Assink and Lammert de Bruin, many thanks for the amazing podcast and your visit to my house, I really appreciate that I could be part of your interesting documentary.

Links:

- Book by Willem Oltmans about his investigation into JFK’s murder: complete text here

(and this is the English version, published much later) - Comprehensive biography of George De Mohrenschildt: here

- Listen to the Dutch podcast: here

Would have been nice if they had contacted me seeing as I produced the long-intended English translation of Oltmans’s 1977 book with the blessing of the Oltmans Foundation and funded by the Dutch Foundation for Literature. In addition I produced the first clearly edited and fully annotated De Mohrenschildt memoir, which De Mohrenschildt based on tapes recorded with Oltmans in the late 1960s.