In the footsteps of Kennedy’s assassin

In 2013, my wife and I visited Dallas and Fort Worth. For the Dutch newspaper Eindhovens Dagblad, I wrote a story about my pilgrimage to the places that were significant in the 1963 assassination case. This is the complete report, translated into English, spanning three full pages.

Click here for a pdf of the article, in Dutch

In the footsteps of Kennedy’s assassin

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Within 48 hours, his suspected assassin was also shot dead. ED (possibly referring to a news organization) employee Perry Vermeulen has been fascinated by the case for years. Half a century later, he embarks on a search for silent witnesses.

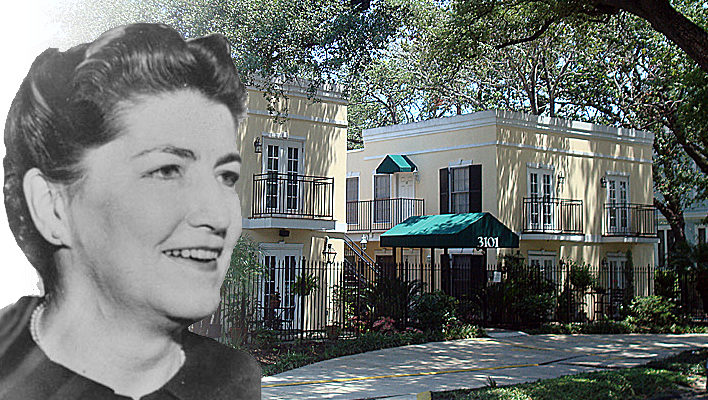

“Get out of my property,” hisses the 75-year-old Kenneth Porter with restrained anger. He is clearly not pleased with the unannounced visit from the Netherlands. The man who married Marina Oswald Porter in 1965, the Russian woman previously married to the alleged assassin of President John F. Kennedy, is accompanied by a loudly barking dog. “Off my land, didn’t you see the warning sign at the beginning of the driveway?” There’s no other option. A conversation is out of the question, let alone a brief interview and a nice photo with his famous wife. “No, you don’t need to try it over the phone either. Get lost, now.”

After a long search on the internet, I had discovered the address a few years ago: a detached house on a large plot near Rockwall, a suburb of Dallas, Texas. Naturally, I had submitted written interview requests, but unfortunately, a response never came. Well, if you’re in the vicinity, you don’t let yourself be deterred by a sign at the driveway. But the message is clear: there’s little to gain here. Apparently, the 72-year-old Marina wasn’t lying when she wrote to an auction house in May 2013, expressing her desire to have nothing more to do with the past. Not without reason, the wedding ring from her first marriage was in the same envelope—the only thing she still possessed from that part of her life. The gold ring, which recently went under the hammer for a whopping $108,000, was placed on Marina’s finger on April 30, 1961. Just over two and a half years later, husband Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested for the murder of the popular president.

Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, 1963. For more than ten years, I have been fascinated by the tragedy. I own a small library on this turning point of the twentieth century and have also written two books, published in 2008 and 2012. Strangely enough, I have never been to Dallas myself. In 2009, I did travel through another part of the vast country, making a bike tour in New Orleans along many significant places in Oswald’s life. I want to repeat a similar pilgrimage, but this time in Texas. How does the murder still resonate there, fifty years later? In August and September, I will visit Kennedy-related exhibitions in Boston, Hyannis Port, and Washington, DC. In this anniversary year, the president is even more commemorated there than usual: in this country, they know how to honor a statesman. But: how strong is the historical awareness in Dallas?

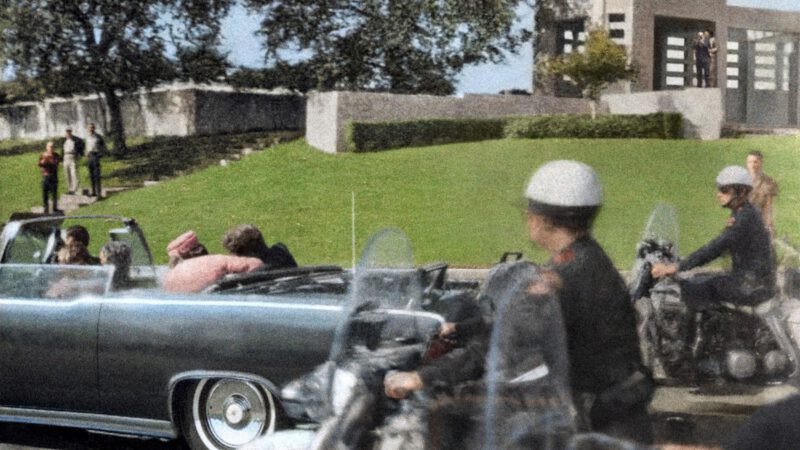

On the usually bustling Dealey Plaza, the crime scene, it’s quite calm on this Tuesday morning. “Few researchers choose to share their theories under these circumstances”, says Mark Oakes. It’s almost 35 degrees Celsius around half past ten. Four tourists listen attentively for some time to the 61-year-old conspiracy theorist, who enthusiastically talks about his in-depth interviews with witnesses of the murder. Two others, slightly apart from the group, point upward. There, behind the window on the fifth floor of the former schoolbook depository, shooter Lee Harvey Oswald was situated. And on the road in front of them, the presidential motorcade drove, heading to a lunch in the Dallas Trade Mart’s patio.

“Oswald was up there, but the fatal shot was not fired by him,” Oakes confidently lectures. “It took me a while to figure out exactly what happened. Don’t be distracted by the tourist signs and the museum. All government propaganda. They ignore all the contradictions in the case.” One of his listeners looks over his shoulder, toward the grassy knoll behind him. According to many, a second shooter would have stood behind the wooden fence. Earlier this morning, Mike Browlow was also telling the story of the murder at that fence—he witnessed it with his own eyes at the age of twelve. “They’ve replaced this fence about eight times already. Tourists keep breaking off pieces of it. Understandable: who wouldn’t want to take home a piece of history like this?”

I’m lucky to come across men like Oakes and Browlow here; they came close to losing a lawsuit against the city of Dallas. The government doesn’t really want people here talking about conspiracy theories and peddling books, DVDs, and magazines about all those possible conspirators. Browlow has never been concerned about the outcome. “No one messes with the right to freedom of speech.”

The Murder

It is very special to be here. The entire square has recently been renovated by the city for several million dollars; every blade of grass has been moved for the commemoration in November. Dealey Plaza is indeed smaller in reality than you think, as I have heard before. Shooting a lethal shot at such a short distance doesn’t seem like a huge challenge. Like many others, I briefly stood on the structure where Abraham Zapruder captured the murder fifty years earlier with his Bell & Howell film camera, but then I quickly walked to the former book depository: the main entrance pulled me like a magnet.

Up in that building since 1989 is the Sixth Floor Museum. The museum welcomes about 350,000 guests each year, but curator Gary Mack expects many more in this special year. The sniper’s nest is separated from curious visitors by a glass wall. On the spot are all book boxes, just as they were at the time of the murder: they formed a nice hiding place. Looking through the window next to it, the distance to the road below doesn’t seem too far. Two men had a lively discussion: why wasn’t there a shot half a minute earlier when the shooter had a much better line of sight? Thousands of pages have been written just about that question. In another corner of the room, a film of Kennedy’s funeral was shown. Two middle-aged American women couldn’t hold back their tears.

The Escape

Lee Harvey Oswald fled after the murder by bus and taxi to his boarding house on the other side of the Trinity River, on Beckley Avenue in the Oak Cliff neighborhood. I spoke with the landlady, Patricia Hall, the granddaughter of the woman who ran the lodging in 1963. As a young teenager, Patricia was there every day, and she knew ‘Mr. Lee’ as a friendly, calm man. “It wasn’t until three days after Kennedy’s death that I found out he had something to do with it,” she said on her porch. “We still have his bed in the same room: occasionally I earn a little extra when tourists come to the door. Our employee Earlene Roberts was extensively questioned by the FBI and the commission investigating the murder. She saw Oswald hastily run to his room, and he left the building again after three minutes, at 13:03. Later it turned out that he picked up his gun here, with which he killed Officer J.D. Tippit thirteen minutes later. Tippit spoke to Oswald because of his suspicious behavior on the corner of 10th and Patton Street.”

Is the distance of 1.25 kilometers walkable in that short time? Could Oswald have killed that officer? This has been discussed for fifty years. With my fast pace, I covered it in less than twelve minutes. Patricia: “Crying teachers, that’s my memory of that black day. I recently put the boarding house up for sale: hopefully, thanks to the special history here, I’ll sell it quickly. Has the tragedy ultimately yielded something good?”

Oswald continued to run after the murder of Officer Tippit, hid his white jacket under a car (the unique garment I saw a week earlier at the exhibition in Washington, DC), and eventually ended up at the Texas Theater on West Jefferson Boulevard without a ticket, taking a bus and a taxi to reach the location in the Oak Cliff neighborhood. Theater employee Julia Postal and Johnny Brewer, manager of the Hardy Shoe Store on the same street, saw Oswald sneaking in and then called the police. At 1:50 pm, after a brief struggle, he was arrested in the theater. The shoe store no longer exists, but the theater still shows movies. “We are regularly visited by people who want to see Oswald’s seat,” says manager Mary Katherine McElroy. “But the interior from 1963 is no longer in use. Of course, we don’t mind if they want to see the relevant hall.”

Within 48 hours, Oswald himself was also killed when he was about to be transferred to the local prison. Nightclub owner Jack Ruby fired his shot in the basement of the Dallas Police headquarters, near the former city hall, about a kilometer from Dealey Plaza. The space is not accessible to unauthorized persons. This part of the center is not very interesting for Kennedy tourists: Ruby’s Carousel Club, a few blocks away, has long since been demolished.

A Paradise for Enthusiasts

I briefly visited Kennedy’s actual destination on that sad Friday in 1963. There is a small monument to the president at the main entrance of the Dallas World Trade Center, but the historical awareness of the employees wasn’t particularly great. Two of the three employees I asked didn’t know that JFK had to speak here back then. No, they had never really looked at the statue at the entrance. If you drive a little further on the Stemmons Freeway, you eventually reach Parkland Hospital. Both Kennedy and Oswald were brought here after the murders. The entrance to the Emergency Room has not changed over the years. On the first floor, a memorial wall has been set up, ensuring that people will be forever reminded of the weekend when the hospital briefly became the center of the world.

Dallas, and actually the neighboring city of Fort Worth, is a paradise for people fascinated by Kennedy’s murder. I stood in Oswald’s desolate backyard on Neely Street, where he posed with the rifle he would later use in the murder. I ate lasagna in the Italian restaurant where Jack Ruby always met the mafia brothers Joseph and Sam Campisi. I was in the hotel where Kennedy spent his last night and at the airport where he arrived in Dallas on that Friday morning. I visited the grave of Lee Harvey Oswald at Shannon Rose Hill Memorial Park: although people are not allowed to point out exactly where the stone is, luckily, descriptions circulate on the internet. I visited the homes of Oswald’s family and acquaintances and those of the murdered officer J.D. Tippit and Jack Ruby. Very special to see all those places in person.

A man gets thirsty from a pilgrimage like this, and luckily, in a city like Dallas, there are plenty of opportunities to quench that thirst. I visited two bars that I definitely shouldn’t skip because, thanks to their names, they have everything to do with Kennedy’s murder. Near Oswald’s grave is The Ozzie Rabbit Lodge, named after Oswald’s nickname during his years in the Marines. Every wall in the dark bar is filled with paintings and drawings related to the tragedy of fifty years ago; there are even some depicting Oswald as a hero. “We like to shock a bit, don’t look any further into it,” laughs bartender Casey Weidmann. South of downtown is Lee Harvey’s, an atmospheric bar with a large porch and a sprawling yard full of picnic tables. The controversial name caused problems in the early years, says bartender Howard Kelley. “We sometimes received calls from protesting neighbors. Oh well, Dallas shouldn’t sweep this dark chapter under the rug. Let’s embrace the events of 1963 and not make a fuss about it.”

Kennedy’s murder is still alive, that’s clear. The planned demolition of another Oswald house on Elsbeth Street recently sparked a long and ultimately unsuccessful protest from many researchers. “Newsweek was here two weeks ago,” Casey from The Ozzie Rabbit Lodge said. Not far away, cemetery worker Jeremy shook his head in disbelief. “I see people looking for Oswald’s grave every week.” Personally, he understood little of the sensationalism, an opinion you certainly won’t find in the vicinity of Dealey Plaza. Walking across the traffic square, a young man breaks the silence every few minutes, loudly shouting. He sells magazines, “with never-before-seen autopsy photos.” I don’t believe much of it; all the images have been on the internet for years, but he knows how to sell his merchandise well. The echoes of the shots reverberated fifty years ago over the square, but the information hunger of many remains unquenchable. The murder of Kennedy: as if it happened just last week.