544 Camp Street: Cuban Grand Central Station

The most intriguing aspect of Oswald’s life in New Orleans remains, for researchers, his connection to a meeting place for anti-Castro exiles, CIA and FBI agents, and members of organized crime. In the office at 544 Camp Street, the paths of these different organizations crossed in 1963. And where did investigators find the address right after Kennedy’s assassination? On the pro-Cuban leaflets that Lee Harvey Oswald distributed in downtown New Orleans. He was a familiar face in the Newman building, as the building was colloquially called, named after owner Sam Newman. I have been to this intriguing location twice, in 2009 and in 2013. Unfortunately, the building at the mentioned address was demolished many years ago.

Not long before Oswald’s arrival, the three-story office also housed the Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC). Alongside Carlos Bringuier, CRC members like Sergio Arcacha-Smith and Carlos Prio Socarras, high-ranking Cubans actively working with the CIA to liberate their country from Fidel Castro, frequented the place. Prio, who had possibly met Oswald’s assassin Jack Ruby through a mutual friend, would be murdered in April 1977 just before testifying before the House of Representatives committee. Although the CRC had left the old complex before Oswald arrived in New Orleans, many anti-Cuban organizations still occupied the address 544 Camp Street. It’s no wonder that those involved jokingly referred to the building as the ‘Cuban Grand Central Station.’

Around the corner, the building had a second entrance with the address 531 Lafayette Street. At this address, the controversial private detective Guy Banister had his office. Banister, born on March 7, 1901, had been a Special Agent for the FBI in Chicago for almost twenty years, dealing with figures like Al Capone and Sam Giancana. After serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI), a precursor to the CIA, during World War II, he unexpectedly left the FBI in 1954. He took a position with the police in New Orleans. Over the years, Banister became more volatile, right-wing extremist, and addicted to alcohol. On June 1, 1957, at the age of 58, he was fired after a weapon incident at New Orleans’ Old Absinth House. From that point, he ran his detective agency: Guy Banister Associates.

Banister, in addition to his connections with CIA and FBI agents, also had close ties with Cuban exiles. Researchers claim that Banister used his detective agency as a cover for activities he carried out as a liaison between the intelligence service and exile organizations. Banister assisted, among other things, in the distribution of ammunition for the Bay of Pigs invasion. The Cubans had a staunch ally in the private detective, as he harbored a deep hatred for communists throughout his life. Banister also disliked the apparent end to segregation and was a racist who disapproved of Kennedy’s increasing involvement in civil rights.

During those years, a frequent visitor to the infamous building was David Ferrie, a man with a tragic life history. He once aspired to a religious career, but alleged emotional instability, related to his homosexual feelings, led his university to consider a religious life unsuitable for him. Eventually, he ended up as a talented pilot at Eastern Airlines. A promising career awaited him until he was fired for engaging in intimate activities with underage boys. After that, he immersed himself in the fight against Castro, becoming a valuable asset thanks to his piloting skills. He also acquainted himself with local mafia bosses. Researchers suggest that Ferrie might have flown mafia boss Carlos Marcello back into the country after being deported to Guatemala by Robert F. Kennedy. In the subsequent period, Ferrie worked for various lawyers of Marcello. Due to illnesses, he lost his body hair at an early age; Ferrie had a distinctive appearance with a red wig and large, fake eyebrows. Despite his eccentricities, he was widely respected by his right-wing extremist friends for his intelligence. In addition to all his activities, Ferrie actively pursued a personal, obsessive mission to develop a cure for cancer, motivated by his own health problems. His house was filled with mouse cages; he used the rodents for his numerous experiments. The kitchen resembled an impressive laboratory.

Ferrie and Guy Banister shared a common trait: a deep-seated dislike for John F. Kennedy. In their eyes, he was a friend of the communists, and with him in power, the fight against Cuba would never be won. Ferrie, in particular, was outspoken; he was even removed from stages multiple times because his speeches became too hateful, offensive, and threatening towards the president: ‘They should shoot him.’ Around 1963, the two men had a close friendship, and Ferrie was often seen in Banister’s office. There are also several reliable sources who later testified that Ferrie worked for the CIA during those days. Ferrie played a significant role in New Orleans within the CIA-coordinated struggle of Cuban exiles against Castro. While Oswald distributed pro-Castro pamphlets in the city, Ferrie led an anti-Castro demonstration a few streets away.

The possibility of a conspiracy behind Kennedy’s assassination becomes more plausible if it can be proven that Oswald had contact with men like Banister and Ferrie. Ferrie always denied knowing Oswald. Ferrie was questioned by authorities and denied everything, including any involvement in activities of Cuban exiles. Interest in the man waned quickly. Only a few years later, when prosecutor Jim Garrison initiated his investigation into Kennedy’s assassination, Ferrie was suspected of being an accomplice in plotting the murder. When this was reported in the news in February 1967, Ferrie’s life was in danger. Within a week, he was found dead in his apartment, officially declared to have died from a cerebral hemorrhage. However, two quite remarkable farewell letters were found near the body, leading to much speculation about the true circumstances of his death.

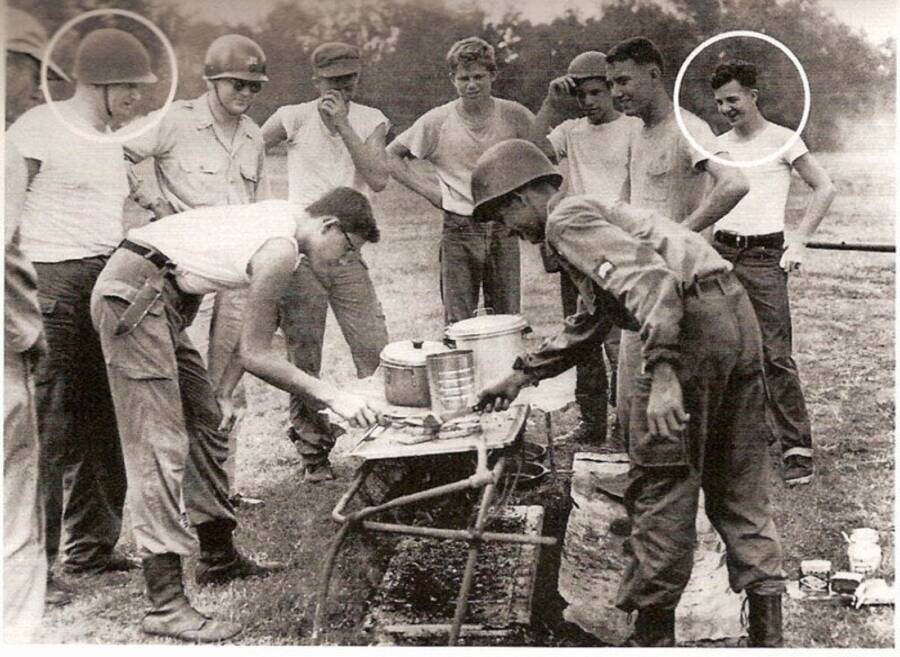

In 1993, an old photo suddenly emerged. Oswald was nearly sixteen when, as an apprentice, he participated in activities of the Civil Air Patrol. Unable to join the navy yet, this was a way for him to be useful. In the 1955 photo, he stands on the far right, watching peers working with a camp stove outdoors. Their leader, David Ferrie, stands almost entirely to the left. It turned out, much later, that Ferrie’s claim of never having known Oswald was a lie. Did they encounter each other again in the summer of 1963?

And then there’s Guy Banister. There are reliable sources that state they were visited by the private detective when they were still students on the university campus. He engaged in discussions with the young people about the rights of white and colored Americans, clearly expressing his own right-wing opinions. According to historian Michael Kurtz, one of those students at the time, Banister brought a young man, Lee Harvey Oswald, to one of these meetings in May 1963. They visited the campus together again, with Oswald passionately supporting Banister. Kurtz later mentioned that he saw the pair outside the campus that summer, having coffee together at Mancuso’s, the coffeehouse on the ground floor of the Newman building. The fact that the two occasionally drank together there was later confirmed by more witnesses.

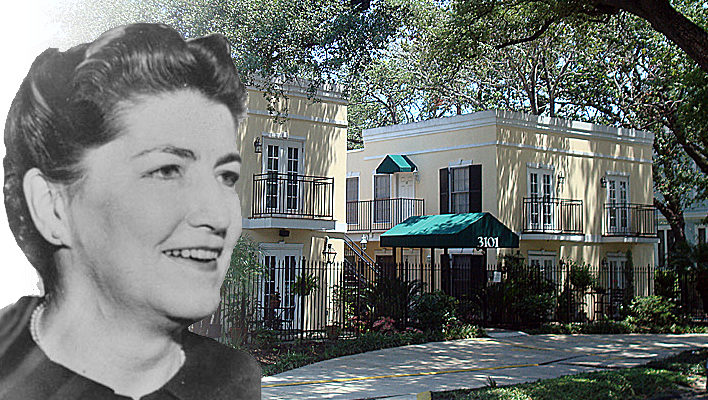

Banister’s employees, Jack Martin, Allen Campbell, and secretary Delphine Roberts, were also certain. Oswald and Banister knew each other, not just by sight. Roberts, being close to the action due to her work, later stated that Banister was aware of Oswald’s leaflets with the address Camp Street 544. Her boss reportedly reassured Roberts, saying, ‘Calm down, he is one of us.’ Roberts’ daughter, who rented a space in the building for photography work, also claimed to have seen Oswald several times. A friend and a brother of Banister testified in the 1970s that Oswald and Banister knew each other in the summer of 1963. Adrian Alba, a friend of Oswald working in the garage next to the coffee factory, also saw Oswald multiple times in Banister’s immediate vicinity. ‘He received financial support from the CIA,’ Delphine Roberts later said in 1978 during an interview with author Anthony Summers. ‘I am sure that in 1963, he suddenly had access to large sums of money and that he often received visits from well-known intelligence agents in the city.’ Banister died in June 1964 at the age of 64 due to a heart attack. He never provided an official statement about his summer with Lee Harvey Oswald.

Another episode connecting the building with Oswald is the statement of anti-Castro militant Ernesto Rodriguez. After Kennedy’s assassination, landlord Sam Newman stated that he was approached by a Latin American man asking if there was an office for rent in the building. The man wanted to give Spanish lessons there in the evenings. Authorities tracked down the man, who turned out to be Ernesto Rodriguez. He admitted to giving Spanish lessons and knowing Oswald, who wanted to learn the Spanish language. Rodriguez claimed that he introduced Oswald to Carlos Bringuier.

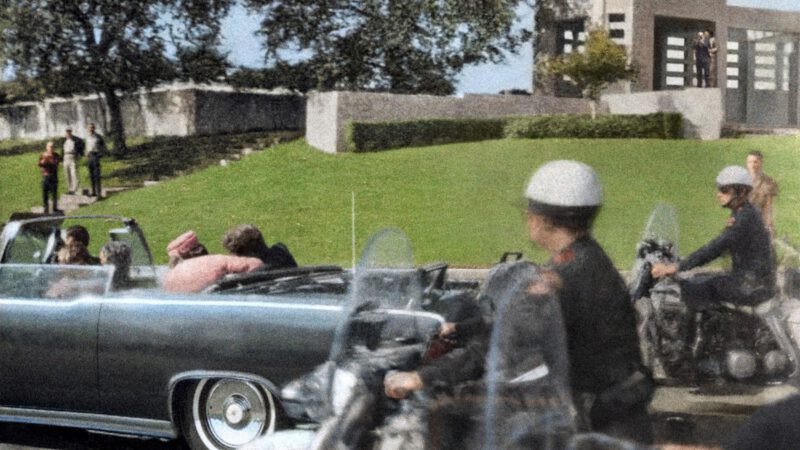

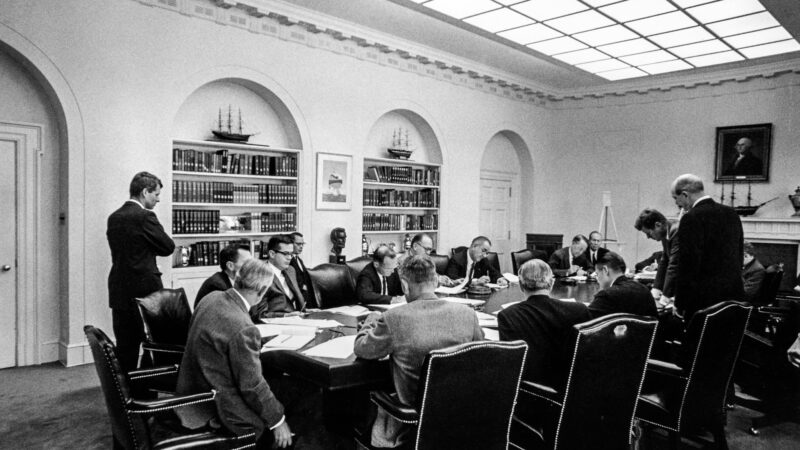

The building served as a base for right-wing extremists, yet local authorities didn’t raise eyebrows when they saw the address on Oswald’s leftist flyers. Serious doubt should be cast on the notion that they genuinely did not notice the contradiction. A lot happened in the building, located in proximity to the local offices of the CIA and the FBI and around the corner from the coffee factory where Oswald worked. Many researchers strongly believe that the plans culminating in the fatal shots in Dealey Plaza, Dallas, were hatched in this building. None of the frequent visitors to 544 Camp Street were questioned by the Warren Commission at the time. Filmmaker Oliver Stone found this bizarre as well. In his film JFK, the events of that summer in New Orleans played a crucial role (photo below).